The Networker has always been a community affair. From our first issue, every glimmer of an idea for an article or theme of this magazine has been a group process with one common goal in what might be called the collective Networker mind: to make it the best magazine we can possibly produce. Every word you read has been conceived by authors (many of them old Networker hands) and editors in tandem, written, perused by several pairs of beady, critical eyes, and filtered by demanding, skeptical brains; rewritten, and often re-rewritten two or three more times; then copy-edited, trimmed, buffed, and polished until, finally, we must reluctantly forgo the ideal of absolute perfection just so we can get the damn issue printed and mailed.

Even 30 years ago, when we called ourselves The Family Shtick, we realized that if we wanted to publish a successful therapy magazine—that purposely was not an academic journal—we had to go beyond accurately reporting on different theories and models, regardless of how worthy. We had to make the magazine something people read because they wanted to, not because they felt that, for professional reasons, they should. It’s always been a kind of communal mantra that what we publish in the Networker adheres to George Orwell’s five rules of effective writing: avoid cliché, never use long words when short ones will do, use as few words as possible, never use the passive where you can use the active, and avoid jargon. Implicitly, every editor at the Networker, past or present, has known and accepted the drill.

Oddly enough, however, until we began working on this issue, it hadn’t really occurred to me that there was a name for what we’d been doing over the last 30 years. I always felt we operated much like a close-knit community, all of us sharing a certain outlook, a set of values and standards, a common vision of what we were trying to do. Now, with this issue, I understand that we are what social-learning theorist Etienne Wenger has called a “community of practice.”

As Wenger has described it, a community of practice is more than a group of friends or network of personal connections. It’s something often formed spontaneously and informally across a vast range of professions, hobbies, arts, and fields of expertise, by practitioners invested in engaging in some activity with increased levels of proficiency and effectiveness. The underlying premise is that we learn more, accomplish more, and become better at something through working together—sharing information and resources, supporting, encouraging, teaching, and challenging each other.

When a community of practice takes the next step to becoming a true culture of excellence, it’s because the right combination of leadership, mutual trust, and standards of competence and achievement has taken hold. What binds these cultures is the recognition that, regardless of our individual contributions, we all need each other to pull off a valuable achievement.

None of this is radical or revolutionary. But in a society devoted to the myth of the self-made man (or woman) and the thoughtless veneration of untrammeled individualism, it bears repeating and has broad applications, especially in the often isolating field of psychotherapy, as we hope this issue will show. Whatever individual qualities and abilities we bring to almost any common endeavor, it’s the synergy of those different but synchronized voices and capacities that make it work. Besides, it’s more fun and satisfying to work together as a clan than to struggle alone, with no company but our computers.

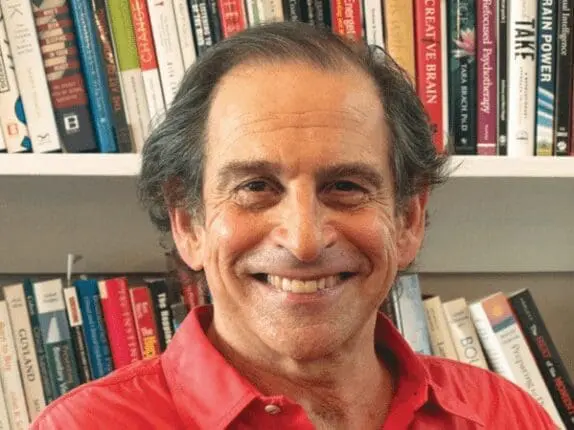

Rich Simon

Richard Simon, PhD, founded Psychotherapy Networker and served as the editor for more than 40 years. He received every major magazine industry honor, including the National Magazine Award. Rich passed away November 2020, and we honor his memory and contributions to the field every day.