When I was a kid, I loved the World Almanac above all other books. To me, it contained everything a well-informed person needed to know: the world’s capitals and largest cities, the longest rivers and highest mountains, the biggest and smallest planets, baseball’s batting champions going back to the legendary days of Ty Cobb and Honus Wagner, not to mention a complete listing of Academy Award–winning movies and all the presidents of the United States. Here was truly a repository for all the world’s knowledge, an explanation for life’s mysteries, a key to the structure of the universe. And, most importantly, it was all contained in one, single, hefty volume.

I think there’s something about the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) that embodies this same kind of appeal for many of us. After all, a book the size of DSM-5, the latest in the DSM series, must contain a world of knowledge. Whatever you might know or believe about its troubled history, the conflicts of interest hounding its production, and the dodginess of its scientific underpinnings, there’s something deeply reassuring about holding in your hand a volume containing a definitive list of every mental illness and experience of psychic suffering that bedevils the entire human species. Forget Euripides and Sophocles, Shakespeare and Dostoevsky—just run your finger down the criteria sets for any of the long list of disorders, subdisorders, and sub-subdisorders, and presumably you’ll find a guide to more calamity, pathos, and plain weirdness than were ever dreamt of by the authors of the literary canon.

For all the abuse the poor old DSM has taken, it brings a much needed sense of order and logic to what’s otherwise a raw, chaotic mess of mental and behavioral phenomena. Undoubtedly, many a therapist—even perhaps some of those loudest in condemning DSM—has consulted it, not just to figure out the most reimbursable diagnosis, but to get some handle on the maddening complexity that clients bring to sessions. If we didn’t have the DSM, would we be reduced to consulting clairvoyants?

Part of the problem with the very concept of a DSM in the Internet world of today is that big, ponderous volumes packed with information don’t carry the old sense of capital-A Authority anymore. It’s been a long time since I even opened up an Almanac—much easier just to look stuff up online, and if I don’t like the first answer I get, why, I can keep looking until I find one I like better!

Even though the grumbling about DSM-5 does seem to have reached some kind of tipping point, it isn’t clear at all what alternative would be any better. Nevertheless, this issue of the Networker grapples with the question of whether we’re nearing the end of the usefulness of a 150-year-old paradigm for thinking about both mental and physical illness.

Of course, it looks as if we’ll have the DSM with us for a while longer, and it’ll continue to be the book we love to hate and hate to love. And as long as it occupies the central position that it does in the everyday life of the ordinary therapist, we’ll continue to have a front-row seat on the mental health field’s most enduringly ambivalent romance.

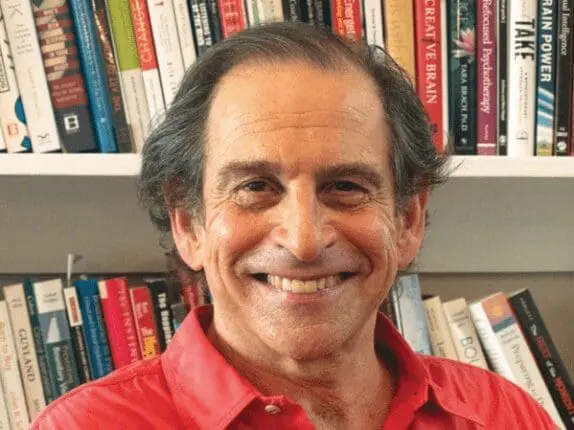

Richard Simon

EDITOR

rsimon@psychnetworker.org

Rich Simon

Richard Simon, PhD, founded Psychotherapy Networker and served as the editor for more than 40 years. He received every major magazine industry honor, including the National Magazine Award. Rich passed away November 2020, and we honor his memory and contributions to the field every day.