During the ’60s, along with other great shifts in that period, the loosening of strictures around divorce represented a kind of liberation from enforced and pressured middle- class domesticity. For many, the new ease around divorce meant greater possibility for sexual expression, personal development, joyous selfhood, and a kind of glorious flowering of, well, human potential. It represented a revolt against everything that was priggish, rule-bound, and in every way buttoned-up about the ’50s—stultifying social conformity, a relentlessly antisexual culture (even very young women got stiff perms and wore crinolines), the rigid dichotomy of traditional gender roles, and quiet desperation tamped down by tranquilizers and alcohol.

Of course, there was a certain amount of hogwash to all this promise and more than a smidgen of libel in the portrayal of ordinary marriage, but a newer, freer world with a greater range of human possibilities was opening up, and easier divorce was front and center. The divorce revolution offered a promise that you didn’t have to live forever with the mistake you made when you were young and stupid: you could be your own person, free and independent, make the best rational choice you could, and if you chose wrong, well, you could always go back and choose again. If that isn’t the America of second and third chances, what is? Sounds a little self- centered and simplistic now, but it was a powerful way of thinking then—and still is in countries where women, in particular, are trapped forever in oppressive marriages.

Over the past couple of decades, we’ve seen a strong and warranted pushback against the idea that nobody should stay in a marriage five minutes after it stops being fun, romantic, and sexy. But if, as therapists, we’re more aware now than our profession was 30 years ago of the social and personal costs of divorce—particularly when kids are involved—helping couples take that momentous step, or help- ing them avoid it, remains an effort fraught with difficulty, ambiguity, and moral significance. No matter how neutral we try to be, our beliefs, judgments, and behavior in therapy can have enormous repercussions on whether the couple in front of us decides to go all-in for saving the marriage or cut their losses and jump ship. Even more disquieting is the reality that our own clinical ideas and attitudes about marriage and divorce are deeply shaped, in ways we usually don’t recognize, by the values of the dominant culture around us.

At this moment in history, we seem to be in a divorce-busting mode, relatively speaking, and so fewer therapists are likely to tacitly encourage divorce as many of us once did. This shift certainly has the weight of traditional morality behind it and probably isn’t likely to begin swinging the other way again any time soon. But this issue of the Networker features some intrepid authors who explore, with an unusual degree of transparency, how difficult it can be to determine what’s in the best interests of clients on the brink of making perhaps the most momentous decision for which therapists regularly have a front-row seat. It’s intended as a reminder of how powerfully we can influence the process, all too often without acknowledging it, even if we don’t have the deciding vote.

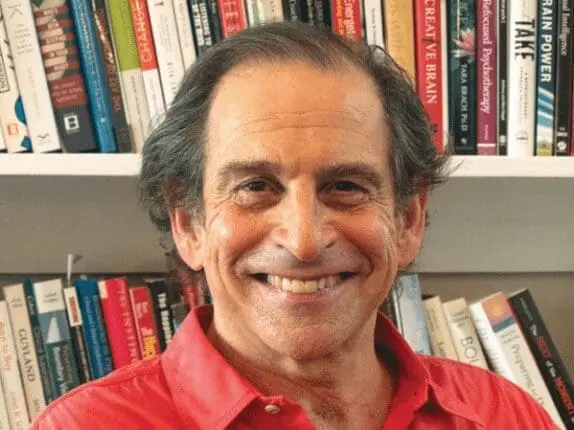

Rich Simon

Richard Simon, PhD, founded Psychotherapy Networker and served as the editor for more than 40 years. He received every major magazine industry honor, including the National Magazine Award. Rich passed away November 2020, and we honor his memory and contributions to the field every day.