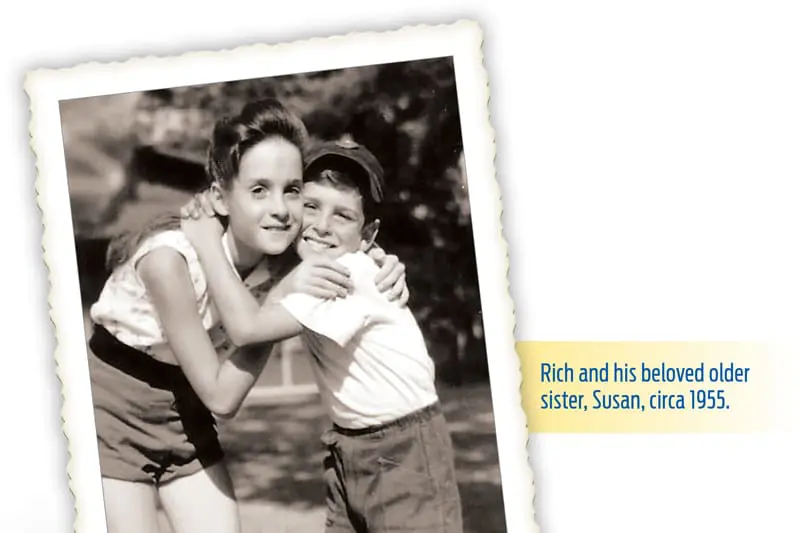

As a young man, Rich Simon didn’t have his sights set on becoming one of modern psychotherapy’s greatest influencers. Inquisitive and erudite, he’d been aiming for a PhD in literature when a chance reading of The Divided Self, R. D. Laing’s classic book about schizophrenia and family dysfunction, so moved him that he signed himself up for a clinical psychology degree instead.

Eventually, his two passions would marvelously merge, when Rich took over a fledgling family therapy newsletter.

What follows is a quilt we’ve stitched together from the thoughts he’d share with readers every decade on the anniversary of the Networker.

This is the story of his life’s work and his passion for not just tracking but investigating therapy’s ever-changing landscape and the wider culture that shapes it.

With Love,

The Psychotherapy Networker Editorial Team

“All therapy is about stories—the stories clients tell therapists and the (we hope) more truthful and helpful stories therapists and clients construct together. Therapy itself is really a story, or stories, about why people suffer, how they heal, and what therapists can do to promote the latter. In a sense, this magazine is a kind of meta-story—or meta-meta story—about all those stories, a narrative in which we’re both the tellers and the told.”

Editor’s Note, March/April 2012

When I first started graduate school, I saw therapy as the individual’s quest for the real, the authentic, the true. Clearly, one’s own family was not the destination in this kind of journey. In fact, I’d spent enough time being under 30 in the ’60s to know that the family was what you needed to escape from in order to discover what you really were.

To my ears, the term family therapy, which I initially encountered in my first year of graduate school, had the disturbing ring of an oxymoron, like peacekeeper missile. It was the least requested course in my training program. But as a first-year student with the lowest status, unable to get into the group therapy course, I found myself assigned family therapy instead.

My training program had a one-way mirror and an observation room. Each week, a bunch of us watched one another repeat the phrases our enthusiastic supervisor phoned in to us, shamelessly pretending a calm and worldly wisdom none of us possessed, to the succession of surprisingly compliant families who’d come to the university’s mental health clinic.

In spite of our fumblings and posturing and crude mimicry of techniques we picked up watching videotapes of the “masters,” our families seemed to change, often dramatically. Each case became its own engrossing story, filled with angry stand-offs, tearful reconciliations, and some sublime moments of laughter and kindness.

During the ’70s and early ’80s, the work had a magnetic appeal for young therapists. This was the first cinemascope therapy, a panoramic vision of human relationships that promised to revolutionize not only the way therapists did their jobs, but the way schools, hospitals, courts, and, indeed, the world worked.

Amid all this excitement and rapid growth, therapists like me didn’t want to hear from authors who sounded like distant experts perched on their podiums. They wanted to hear from colleagues who, like themselves, were experiencing all the exhilaration and uncertainty, challenge and confusion that come with being on a voyage of discovery.

Part of the impetus for starting this publication was to offer on-the-scene coverage of this grassroots movement shaking up clinics, training programs, psychiatric hospitals, and private practices all around the country.

Beginnings

Although our magazine’s date of birth, as in most creation myths, is somewhat arbitrary, we can trace its true beginnings to 1976, when psychologist Chuck Simpkinson started The Family Shtick, a mimeographed newsletter for therapists in the DC area. In 1979, he and I renamed it The Family Therapy Practice Network Newsletter, and, with considerable trepidation, I turned on my tape recorder at the Georgetown University Family Center for a face-to-face interview—my first—with the formidable family therapy pioneer Murray Bowen.

Awed by this first close-up look at one of psychotherapy’s Great Men, my main contribution to the “conversation” was a metronomic head nod while I kept vigilant watch over the tape recorder to make sure it captured each precious word.

At this time, our little newsletter was beating the drum for the game-changing potential of the “systems perspective” and published plenty of articles about the craft and theory of family therapy, but what drew people to us in those early days was probably less intellectually exalted—our unabashed fascination with the colorful personalities attracting such attention on the family therapy workshop circuit. Unlike traditional psychodynamic therapists, who kept a modest profile, these showstoppers commanded—even invited—a kind of hero worship and loyalty that, more than anything, explained the burgeoning field’s popularity.

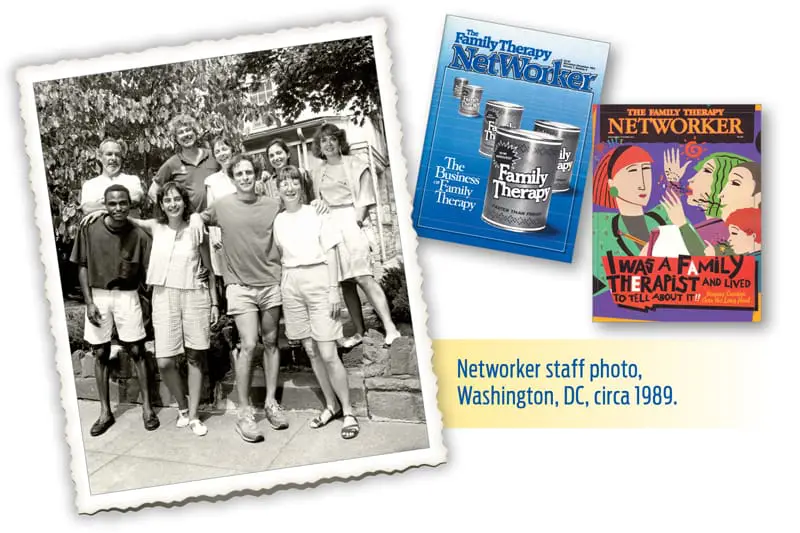

I spent the next few years interviewing and profiling these heroes and surrogate intellectual fathers, and in January 1982, we officially became The Family Therapy Networker. Our first issue—40 pages printed on butcher paper, with a black-and-white drawing of Milton Erickson on the cover—was edited on a typewriter in my basement. I was 33 and had recently quit my job at Karma Academy, a somewhat oxymoronically named treatment program for adolescents. The Networker had a circulation of 300 and a staff of three. Reagan was in the White House, and the Berlin Wall was still standing.

In those days, nobody I knew had computers, and nothing in our little publishing world was digitized. Pages were laid out by hand—photos and galleys waxed and pasted onto their meticulously measured spaces on large, heavy sheets—and then couriered over to the printer. I was still so mired in the early 19th century that I’d never learned to type, so I had to hand-write my “Letters from the Editor” and articles, schlep the drafts to a professional typist (a 15-minute drive), then retrieve them, mark them up, and return them to be retyped on her IBM Selectric.

I didn’t think of the Networker as a business proposition. It was a calling—some who knew me then would say an obsession. I’d become fascinated with the profound and earth-changing truths family therapy seemed to embody. If you put a family in a room together and could understand things systemically, all kinds of magic could happen.

Family therapy also represented a cultural counterweight to the rugged individualism of the Reagan years. Drawing on the social ferment of the 1960s and the community psychiatry movement, we took a broad view of the influence of social context on individual difficulties. I fully expected that, over time, family systems work would consign all other therapeutic approaches to the realm of musty antiques.

In fact, once we left pathologizing diagnoses and emotional archaeology behind, there were no limits to what might be accomplished: our work might even trump the culture of poverty and cure schizophrenia! That optimism wasn’t the product of an ivory-tower intellectuality: it emerged from the dramas that unfolded daily in therapy rooms, before one-way mirrors, and on training videotapes. And this wasn’t just happening in some Esalen hothouse, but with real families around the country—at the Ackerman Institute in Manhattan and the Mental Research Institute in Palo Alto, and with inner-city clients at the Philadelphia Child Guidance Center.

These places were the outposts of an intellectual, therapeutic, and social movement that seemed truly groundbreaking. It was not yet apparent exactly how that movement would change the world, but to the enthusiasts amongst us, it was clear that it was going to. Anything could happen, and, like many therapists, I remained immensely curious about the charismatic thinkers, practitioners, and polemicists leading this movement.

Movers and Shakers

Despite their theoretical and clinical differences, what this entertaining group of iconoclasts shared was a certitude that they could detect the soft, pulsing, inner reality of the families they treated and rapidly transform it with a confidence that would be hard to find among the more cautious clinicians of today. Most of them rejected theory and standard research practices as irrelevant, secondhand knowledge about human interactions that could never convey the direct, ever-shifting experience of therapy in the flesh. These were the action heroes of therapy, demonstrating a flair and sure-footedness that mere mortal therapists found dazzling. After 100 years of reserved, cerebral psychodynamic types, suddenly, our profession was home to a cast of riveting performers.

One of the most influential of these gurus was the cool, hyperpragmatic Jay Haley. An acerbic polemicist and the field’s closest link to master manipulator Milton Erickson, Haley saw the clinician as a wily strategist, who should make use of the power of the therapist’s position, without any nonsense about clinical neutrality or superfluous displays of empathy.

In a 1982 Networker interview, he proclaimed (albeit in a way that may now read like misogyny) that theories were usually more about why things stay the same than how to change them. “You might be able to understand what keeps a man drinking by looking at how his wife provokes him and see how she provokes him because he drinks. But it’s very difficult to see in that description anything that helps you make an effective therapeutic intervention… Being a therapist means not just looking at why things are what they are, but taking a position of responsibility about things being one way or another.”

It’s hard to imagine a figure from that time more unlike Haley than the spontaneous and unpredictable Carl Whitaker, who embodied the kind of quirky authenticity celebrated in the human potential movement of the ’60s. He professed to do therapy because he couldn’t do anything else. For aspiring free spirits, he was the go-to role model of the day.

Whitaker’s work favored accessing the secret labyrinth of the family’s unconscious life through a “method” of weird non sequiturs, off-the-wall challenges, gentle ridicule, and impossible directives.

One story involved an irate, paranoid patient who once told Whitaker, “I’m going to get you and you’ll never know when it’s coming. One day, you may be standing at the urinal and a steel club will hit your head. What do you say to that?” To which Whitaker replied, “Thanks for helping me. Up until now, all I had to worry about at the urinal was getting my shoe wet, but you’ve given me something else to think about.”

Perhaps nobody I interviewed had a greater sense of diva-like certitude or put on a more exhilarating show than Mara Selvini Palazzoli, leader of the Milan Team, a group of therapists whose work offered the purest expression of heady systems principles.

Entering the family therapy field in the ’70s, her interventions offered deeply troubled families complex, double-level paradoxes warning them against the dangers of change. But then in the ’80s, she and her group switched and began issuing a series of “invariant prescriptions,” or fixed directives. The most famous of these advised the parents to disappear from home for as short a time as three hours and as long as three months—without warning or explanation to their children. Since the families for whom this intervention was intended usually included a teenager diagnosed as “schizophrenic” (she tossed the word around with carefree abandon) or “anorectic,” the order threw families into an uproar. This was, of course, just the point—intended to break apart seriously dysfunctional coalitions between children and parents.

When asked whether it bothered her that she hadn’t stayed faithful to the model that had made her famous and had taken up with an even flashier one, she said grandly, “I am not interested in what I said 10 years ago. But this is typical for me because I have the tendency to despise everything I have already done and to be interested only in what I will do in the future.”

For many people, Virginia Satir was family therapy, the very embodiment of the optimistic, can-do spirit that launched the movement. The foremost woman among the field’s founding fathers, she seemed to tap effortlessly into people’s hidden emotion and turn the too-often stilted, diffuse rituals of therapy into exhilarating celebrations of people’s ability to transform their lives. You didn’t go to one of Virginia Satir’s workshops just to listen to her present or interview a family. There was something more. Even as you sat hidden in the anonymity of a large audience, she had a way of slipping past your guard and getting to you. Whether she was making you squirm by having you stare deeply into the eyes of the complete strangers sitting around you or just going on in that friendly, enormously reassuring voice about the untapped potential in every person, she refused to let you remain at arm’s length.

In an early Networker interview, she said, “When people come to see me, I don’t ask them if they want to change. I just assume they do. I don’t tell them what’s wrong with them or what they ought to do. I just offer my hand, literally and metaphorically. If I can convey to the person that I’m trustworthy, then we can move and go to the scary places.”

No leader in the field seemed to communicate more of a sense of social mission than Salvador Minuchin, who also was recognized as family therapy’s most imitated maestro. In his work with poor families at the Wiltwyck School for Boys and later at the Philadelphia Child Guidance Clinic, he seemed to feel that his mandate went beyond therapeutic innovation to broader social change. Here’s how I described my first glimpse of him in a workshop I attended as a young therapist right out of grad school: “Standing in front of the audience of 200 therapists, Minuchin, a compact, dapper man with a Spanish accent as thick as his black mustache, exuded an air of brusque command at odds with the traditionally pacifist culture of psychotherapy. Heaven protect anyone who stumbled through a lame question or tried to say a kind word about psychoanalysis. He seemed to me the most confident persona I had ever met, as if he had been to the mountaintop, seen the Truth and discovered he was It.”

For example, in one classic demonstration, he was working with an impoverished single mother who couldn’t control her defiant eight-year-old son. After spending some time with the two, Minuchin asked the boy to stand up, saying, “I am still trying to figure out what makes you so powerful.” The boy stood up, grinning, and after complimenting him on how strong and healthy he looked, Minuchin asked the mother to stand up, too. As she towered over her small child, Minuchin asked, “Where did he get the idea that he is so powerful? He is a healthy boy, but look, he is just a little kid who somehow has convinced you that he is much older than he really is.”

It was, I learned later, one of Minuchin’s favorite gambits, but as I watched it unfold, I was stunned by both the power and the sweetness of the moment. Both mother and son were smiling, basking in the attention they were receiving, coming more fully alive as if renewed by the prospect of order being restored in the family.

Through family therapy’s formative years, he became the standard against which therapists measured their best work, and when they failed miserably or were confused about how to handle a case, they asked themselves what Minuchin might have done in the same situation.

Therapy’s ‘People’ Magazine

As we focused on covering therapy’s stars, my friends began affectionately calling us the People magazine of psychotherapy. What we wanted was to be intellectually demanding and irresistibly compelling at the same time; to write in kitchen-table English free of journalese and boosterism; to embody complicated ideas in the flesh and blood of everyday life; and, perhaps most of all, to capture the immediate experience of what it meant to be a therapist in this heady time.

By the end of 1982, our circulation had grown fourfold. Our annual meeting, the Networker Symposium, had outgrown first a chapel auditorium and then the local university conference centers, eventually moving to Washington’s grand Omni Shoreham Hotel, where 2,000 therapists attended that spring. We finally had enough money to print full-color covers on glossy paper. No father of a newborn ever felt more pride than I did when I first cast eyes on what finally looked like a real magazine, rather than a glorified pamphlet.

By then, family therapy was no longer the new kid on the block, and I’d interviewed all my father figures at least once. The magic had begun to fade. As we became increasingly aware of larger systems that constrain change, the tone of our coverage of the field began to shift. We grew more skeptical of miracle cures and instant transformations, and even congratulated ourselves on outgrowing our adolescent awe at the older generation of masters.

Power Shifts

If there’s power in determining whose stories will be told and whose believed, the balance of power was tilting within the world of psychotherapy. Mirroring changes in the culture as a whole, women—many of them social workers, rather than psychologists or psychiatrists—had flooded into the profession. Now they were finding their voices and attacking therapy-as-usual as a prescriptive, mother-blaming male ego trip that too often colluded with widespread gender inequities.

If family therapy’s early masters had been my surrogate fathers, the members of the Women’s Project in Family Therapy—Betty Carter, Peggy Papp, Olga Silverstein, and Marianne Walters—were my loving and cantankerous aunts, offering a stinging feminist critique of the field and many standard clinical practices we’d never questioned. Because they were family, we had to listen. We had no choice—what they were saying was not only passionate, but it carried the ring of a long-denied truth.

In the “bad old days,” they argued, therapists (most of them male) had been seen as infallible experts, wielding an emotional power over clients that was destructively unbalanced. Far too often, a family’s problems had been forced into a classic paradigm positing an “enmeshed” controlling mother, a distant peripheral father, and a symptomatic child. Male domination, wife-battering, incest, and the subordinate economic role of women in the larger culture had been ignored. And too many panels at professional conferences (the Networker Symposium included) had consisted of some variation on the formula of “four men and Virginia Satir,” as Betty Carter once put it.

My male mentors had looked at families from the outside. These women wrote and spoke with the sense of having actually lived in families. They were not afraid to talk about their own real lives. Between 1987 and 1992, their writing in our pages deftly integrated the world of the “expert” with the world of the experienced. “Often I felt dumber than dirt,” wrote clinician Molly Layton, describing raising her own children, in her article “The Mother Journey.” “The mother is the object, the bull’s eye, of her children’s feelings, some of which could stun an ox. She is intensely loved, hated, seized, ignored. I was thunderstruck by the blunt distortions my children made of my motives, and then at other times struck by their keen accuracy. In writing this, it occurs to me that they might say the same of me.” This was the inside story.

Secrets Writ Large

In magazine after magazine, we’d begun to focus on topics and social issues not previously considered in the consulting room—race, domestic violence, social class, ethnicity—tackling subjects that most clinicians hadn’t thought relevant to their work. And in the increasingly psychologically attuned, tell-it-all ’80s, in which seeking therapy had become a kind of de rigueur new rite of passage, all sorts of once-taboo subjects were being addressed for the first time.

The lid to the Pandora’s box of family secrets was exploding open, not just in therapy rooms, but in the recovery movement and self-help groups around the country. It was a Vesuvian eruption of revelations, touching on just about everything—alcoholism, drug addiction, infidelity, eating disorders, sex abuse, and incest. These formerly undiscussed subjects became a mainstay of daytime TV. Phil Donahue, Oprah, and Sally Jessy Raphael shared the wealth with tens of millions of viewers. Psychotherapy had become a window on changes reverberating through society, and the Networker was in the thick of it.

If there was one secret revelation that overshadowed the others in the sense of shock and horror it evoked, it was surely the recognition of the widespread incidence of incest. Beginning in the late ’70s, the feminist movement made it possible for hundreds of thousands of women to share their long-hidden stories of childhood sexual abuse—and be believed. Soon thousands of women and men were telling the world about the traumatic sexual abuse perpetrated by their parents or other relatives. Commercial publishers quickly realized the potential marketing bonanza of this hot potato and books proliferated, filling whole sections of bookstores. The term recovered memory entered the popular lexicon, as did the name of a once-rare diagnosis, multiple personality disorder, the presumed sufferers of which began to fill entire wards of psychiatric hospitals. The abuse chronicles reached a kind of dark apotheosis with the bizarre, widely broadcast tales not just of incest, but of satanic cults whose members used children in ritual acts of rape, torture, and murder.

With relatively little up-to-date research and almost no clinical tradition to rely on, therapists seeing these difficult cases were flying by the seat of their pants. The “excesses” of some therapists, as well as the sensationalized prosecutions and trials of parents accused of having years earlier abused their now-adult children, or taken part in grotesque satanic sex and death rituals, grabbed the headlines while steady, patient, careful work by mainstream therapists went unnoticed.

In March 1992, a group of stunned parents declared their innocence and formed a support and advocacy organization called the False Memory Syndrome Foundation. Its members vented their fury at unethical, badly trained, credulous and/or manipulative therapists who used dodgy clinical techniques to elicit false disclosures of incest from essentially brainwashed clients. At the same time, psychotherapists who treated adult survivors found themselves defending their clinical integrity from what they often regarded as, at best, the reactive denial of accused parents, or at worst, a cynical, orchestrated attempt to once again suppress the truth about widespread child abuse.

In 1995’s “Caught in the Cross Fire,” Networker features editor Katy Butler captured the disorientation many clinicians were experiencing, writing, “Some therapists believed every memory of satanic ritual abuse as gospel, passed around their own invented statistics, misused hypnosis, overdiagnosed, and drew heavily on self-help literature and pop psychology… If the influence of past abuse had gone unrecognized by the old paradigm, those involved in the new paradigm would focus on it to the exclusion of the present… If earlier therapists had tacitly colluded with abusing fathers and mothers, they would now champion the daughters and sons. These were the excesses.”

Critics began to claim that the banalities of psychobabble and the “abuse excuse” were undermining individual responsibility. They said psychotherapy was creating a culture of victimhood, which, instead of helping people acknowledge the past and then move on, was keeping them stuck in the victim role. Increasingly, as the decade progressed, those criticisms came not from outside the field, but from within it as well.

Commentators began discussing an imbalance afflicting the field that led many therapists to focus almost exclusively on their patients’ suffering, rather than their strengths and resilience—often encouraging the endless reliving of old trauma and reinforcing the survivors’ sense that they were deeply, perhaps irretrievably, wounded. But as psychotherapist Dusty Miller, a survivor of child abuse herself, wrote in these pages, “The ripples that flow outward from every traumatic event don’t have to sink us, or assign us a single identity. Victim describes a specific moment in time, not a permanent self-definition. This is a comforting aspect of the impermanence that transforms every emotional state.”

We began exploring the notion that “objective reality” did not exist apart from the perceiver’s “narrative” of it. And the therapist’s narrative—conditioned by upbringing, social standing, and point of view—was only one story among many. In the early ’90s, our newest editor, Laura Markowitz, widened the lens, bringing in narratives long left in the cultural shadows and shabbily treated by therapists: those of people of color, people in the LGBTQ community, and members of other marginalized groups who questioned and expanded our definition of “family.”

Heady Times

On a bright April afternoon in 1993, our staff, dressed in our cosmopolitan best, sat nervously at a banquet table in the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York in the august company of the editors of magazines like The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Harpers, Fortune, and Vanity Fair. When we were announced as the winner of the National Magazine Award for Public Interest Journalism—the magazine industry’s version of the Oscar—I climbed the podium to accept the award and made a joke about being one of the few therapists who had never treated Woody Allen. Our homemade magazine with the awkward name had beaten out Consumer Reports and U.S. News & World Report, among others in our category, with a special issue on the dogged survival of the community mental health movement. By now we had a full-time staff of six and had moved out of the basement of my DC home and into offices next door.

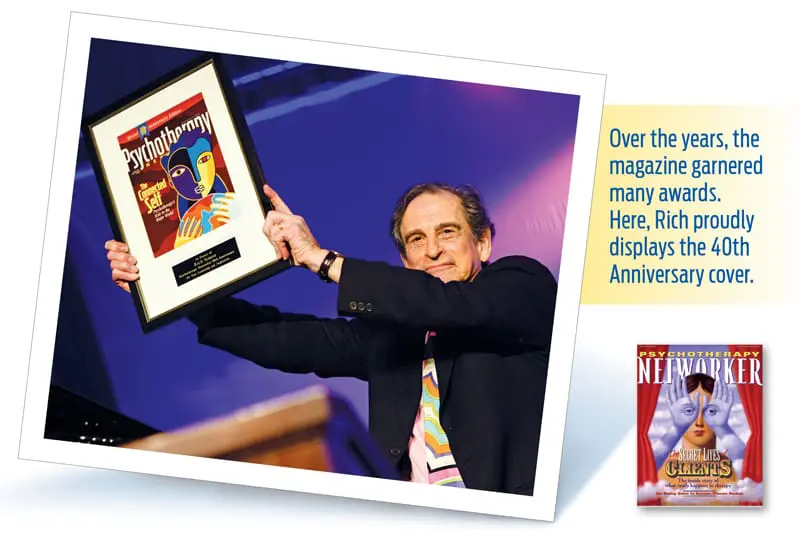

Over the next three years, we garnered three more National Magazine Award nominations, three Utne Reader Alternative Press Awards, as well as three Folio Editorial Excellence Awards, and a wall full of other honors. The wider world of big-league journalism had discovered us. An issue on narrative therapy became the basis of a report in Newsweek, and an investigation of EMDR by our editor Katy Butler was picked up by New York Magazine, Newsweek, and ABC-TV’s 20-20.

They were heady times, but they didn’t last long. The unexpected recognition by mainstream journalism mirrored the fact that our profession was on the crest of a cultural wave. Therapists, once the bearded objects of parody in Feiffer cartoons, had quietly supplanted priests as the culture’s resident sages. Just as we were losing confidence in the primacy of the therapeutic narrative, much of the culture was appropriating the language of the field as a whole.

In the White House, William Jefferson Clinton had become the nation’s first Therapist-in-Chief, and his vice president had acknowledged on national television that he and his wife had benefited from therapy after a family tragedy. One study indicated that one American out of four had received some form of psychotherapy. As a publication, we’d just gone through a period of learning what it means to take a broad view of the influence of social context on individual difficulties; now the wider culture was busy reducing a range of social and political issues to the expressive individualism and contractual ethics of psychotherapy.

The Tide Turns

We’d hardly caught our breath and said “It’s more complicated than that” when the tide turned, and we found ourselves covering a cultural crisis of confidence in the values of psychotherapy. Therapy—that entrepreneurial, ad hoc, quasi-scientific venture—had operated for decades with few constraints and generous third-party insurance reimbursements. Now, critics were saying we were splitting up families, promoting a culture of victimization and reproach, overselling our work, pretending to be a science, and providing no moral vision while usurping the authority of moral leaders. The revealers of the cultural shadow had turned out to have shadows of their own.

By 1998, the Networker had joined the information age. Like families and work groups throughout the culture, we uneasily embraced the Faustian bargain of geographical freedom, misunderstood email jokes, and melting boundaries between work and home. We were participants in what contributing editor Michael Ventura had eloquently called “The Age of Interruption.”

Again, we were a mirror of larger cultural changes: technology had increased an erosion of family meals, rituals, connections, and “quiet time” underway since baby-boom women had gone to work outside the home, returning each night to an unsupported “second shift” at home. As work weeks lengthened and deadbeat dads proliferated, middle-class families began to fracture in ways that were reminiscent of the families in the disadvantaged neighborhoods that had been one of our first foci of concern.

We became less sanguine about the ability of family therapy—or any kind of therapy—to trump enormous cultural and economic pressures, even among well-educated, middle-class clients.

Today, much of what the Networker once heralded as earth-shattering has either melted into the larger culture, been quietly jettisoned, or taken as a given. Few people try “leaving home” therapy with schizophrenic clients anymore. As for the community psychiatry movement, many of those particular former clients now live on the streets. The Philadelphia Child Guidance Center has disappeared, and former director Salvador Minuchin has said, “The slum rather than the families eventually prevailed.”

We have made our peace with much of what we once assumed would become clinically obsolete: cognitive-behavioral therapy, biological psychiatry, psychoeducation-skills training. At the same time, many of us have made a restless peace with larger systems, such as managed care, that shape our own practices and our clients’ lives.

In 2001, after much agonizing, we changed the name of the magazine to Psychotherapy Networker to reflect our humbled, mid-life curiosity. We’d come to see that not only is the family a system, but the profession is a system, and there are systems inside systems stretching out through time, influencing each other and nested within each other like Chinese boxes: the intricate systems of the body’s neurochemistry, so easily influenced by trauma and physical diseases like diabetes; behavioral preferences encoded in DNA; larger, almost invisible systems of social influence embodied in the cellular phone and in full-page color ads promoting Prozac in the pages of Health magazine.

Through it all, we still try to be an honest witness, critically examining anything that might be helpful to therapists and their clients. When looking at a possible article, I continue to ask the questions that have helped guide me ever since I first edited a Networker interview in my basement in Tyson’s Corner: What’s new about this? Is it interesting? And what part of the larger story—however uncomfortable it may be to acknowledge—are we leaving out?

Meanwhile, the story continues, with all its unpredictable plot twists and character developments, its villains and heroes. As we step forward into the uncertain future, I still take my guidance from Sal Minuchin, my first hero. According to him, no matter what case he was seeing or how much he continued to learn about what works in psychotherapy, one thing remained the same: “I’m always saying to people, in one way or another, ‘There are more possibilities in you than you think. Let us find a way to help you become less narrow.’” At another time, reflecting on the ups and downs of his own long career, he said, “I have failed in many ways, as most clinicians do. But when you fail, your certainty is transformed into questioning. I still see myself as an expert, but I know my truths are partial truths and my style of intervening is partial. Perhaps real wisdom is the uncertainty of the expert.”

Recently, I was having dinner with my daughter and several of her millennial friends at a trendy New York restaurant. One young woman proudly told me that she was the longest-serving employee at her start-up company—she’d been there five whole years, a virtual lifetime in her worldview. When I told her that I’d been employed at the same outfit in the same position for 40 years, she looked a bit alarmed, as if the incarnation of some Old Testament figure had suddenly appeared beside her. How was it possible to spend that much time doing, more or less, the same job?

In truth, I sometimes wonder the same thing. Have we at the Networker really been doing the same thing for scarily close to half a century? Maybe we’re still so fully engaged in what we do because, even after all this time, we’re still seeking the ingredients to the elusive magic formula (or formulae) that will dependably resolve more of the complex issues clients bring to us.

Every Networker issue begins with an incipient idea, often vague and hardly formed, that may come from any one of a hundred sources—a note from a reader or one of our writers, an article we’ve seen, a conference we’ve attended, a news story. Once the thought is embedded in our collective brain, we call around to different members of our extended professional tribe to develop this fragile, sometimes fleeting, bit of inspiration.

At the end of the intense and unpredictable process, as we’re holding an alluringly bright and shiny new issue in our hands, we feel once again, as we have for all the past issues, a sense of giddy astonishment. And perhaps with unwarranted pride, we feel that we’ve produced something that matters, not only to our profession, but to the wider world—because every issue is, in its own way, a celebration of the human capacity to make new discoveries and add further contributions to this vast, perpetually unfinished story that connects us all.

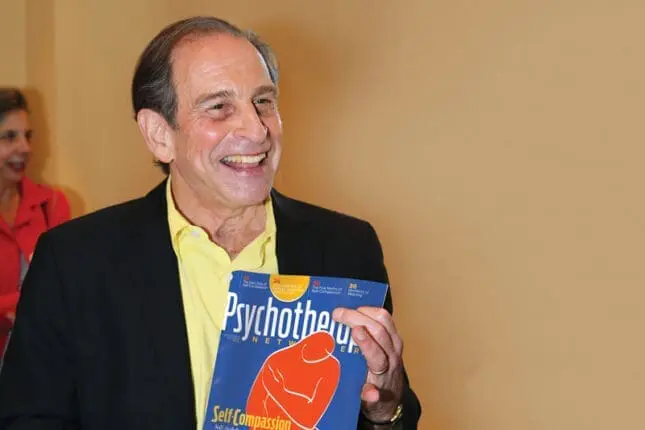

Lead Image: At each Networker holiday party, Rich celebrated issues from the past year, as he did with this one from 2015. Courtesy of Jacob Love.

Rich Simon

Richard Simon, PhD, founded Psychotherapy Networker and served as the editor for more than 40 years. He received every major magazine industry honor, including the National Magazine Award. Rich passed away November 2020, and we honor his memory and contributions to the field every day.