We’re at a corner table. I’ve just shared stories about several friends remembering sexual assault experiences of their own while watching the Brett Kavanaugh trial. As the waiter sets our tea service down in front of us—kettles, cups, saucers, spoons—my mom says, with an awkward chuckle, “Well, I had a memory come back, too.” The waiter—does he sense a shift?—stiffens. He avoids our eyes, turns on his heels, and walks away wordlessly.

“What is it?” I ask, pouring tea.

“I don’t know,” my mother hesitates. “It’s a heavy topic.”

Our lunches have unspoken rules. Keep it light. No raising your voice. Avoid difficult subjects, like her ex-husband—my father. Stay seated, even when you’re tempted to walk out. No complaining, especially about each other. And the cardinal rule: be nice.

We’ve managed to follow these rules, with only a few lapses, since I was a teenager. My mother worked as a fundraiser for most of her life. Once, in a moment of adolescent pique, I called her a glorified beggar. Another time, she stormed out of the restaurant because I insisted she’d always cared more about her friends than me. On several occasions, we unleashed accusations in embarrassingly self-righteous verbal attacks, each of us convinced we were the true victim of our mother–daughter narrative.

But that was years ago, before I stopped drinking, became a therapist, and had a child of my own. Motherhood has humbled me. It’s helped me appreciate the complexities of caring for another human being when sometimes I struggle to care for myself.

We’re civilized now. My mom lifts her teacup.

“It’s not a heavy topic,” I insist. “What kind of memory?”

“I modeled for artists in New York,” she says. “Painters, mostly. It was the ’60s. I was fresh out of college. An agency sent me out on assignments to work at studios and art schools.”

“Sounds risqué,” I began with a smile, but stopped when I noticed her eyes.

“It was risky, I suppose, especially then.”

Her hand trembles as she refills her cup with tea. Maybe it’s because we’re near the window and there’s a chill. Steam rises in feathery coils.

“I can imagine,” I murmur, fiddling with my own cup to keep my hands occupied.

Gray hair falls around the folds of her ears and face. It’s poignant to imagine my mother young. I still have a picture of us in a French bistro in Georgetown at one of our first lunches there in the mid-’80s. The bistro has been gone for more than a decade, replaced by a Starbucks. The picture—itself a relic of pre-selfie, pre-cellphone mementos—shows us sitting on opposite sides of a checkered red-and-white tablecloth. My mom’s hair is brown. Her teeth are perfect. I’m wearing a lace dress, one of many I used to cull from musty-smelling estate sales and vintage clothing stores in search of a new identity.

My mother and I were strangers then, though we lived in the same house. Our relationship seemed to have skipped over some critical developmental stage, growing itself around a core of emptiness. I blamed her for this fundamental flaw in our bond, and overtly expressed my hostility throughout my teens and well into my 20s. But I was also a sucker for haute cuisine, and the promise of a fancy salad in a lively, upscale eatery went a long way toward softening my anger. Our unspoken deal went something like this: good food in a classy venue in exchange for a semblance of connection. It wasn’t an overt bribe, but it came close. Every few weeks, at lunch, I faked it. She paid the bill. For an hour or two, we got along.

Now I don’t have to pretend. I appreciate her good qualities. There’s a reason why bank tellers and clerks, her friends and my friends, fellow travelers on buses, planes, and trains, all can’t help liking her. She’s attentive and generous. Even in the midst of my lingering resentment, I recognize the value of muscling through our awkward silences and spending time together.

“I was sent to an artist’s studio in SoHo,” my mother continues after a long pause. Her face looks even more disconcertingly innocent, despite crow’s feet and worry-lines and crooked reading glasses on the bridge of her nose. “He was a middle-aged man. He painted me, and afterward he walked over and . . .” She glances down at her bare hands with their chipped nails and age spots. Her face collapses ever so slightly, then her mouth twists into an apologetic smile. “I didn’t mean to cast a shadow over our lunch,” she says.

“Mom,” I say plaintively, “you’re not casting a shadow.”

She stares at me in the deer-in-the-headlights way I’ve grown accustomed to. “Well then, I’m pretty sure he raped me,” she says, her voice stoically matter-of-fact.

I reach across the table and take her hand even though her words haven’t fully registered. I know what they mean, of course. It’s not like I haven’t heard plenty of other people say them—friends, clients, acquaintances, celebrities on social media and television.

But this is different.

“I’m so sorry, Mom,” I say.

Her skin feels cool. There’s a long silence. She blinks.

I imagine her reclining on a dark, velvety blanket spread over a couch in an industrial loft, big windows overlooking Hudson Street or Broadway. An only child of middle-class parents, she wants more for herself than what she’s experienced in her stuffy, all-girls college, more than what her own mother had. I imagine a man stepping out from behind an easel.

“It’s strange I forgot about that all these years,” she murmurs, looking distracted. Tears gather along the rims of her eyes. “I guess you’re used to that with your clients.”

I shrug, trying to find my voice, but it’s stuck in my throat.

The image of my young, vulnerable mother in a stranger’s loft has unexpectedly morphed into other images: me as a 13-year-old in a vintage dress, trying to keep a neighbor’s hands off my legs; me in my history professor’s apartment in college, cops knocking at his door; me closing my eyes as a famous journalist who can’t take no for an answer pins me down.

One of my legs has started vibrating under the table. What if, when I was younger, instead of sitting in silence in the car together, or singing rounds of folk songs on camping trips, my mother had remembered this painful experience and shared it with me? What if she’d explained how it had happened to her, and how easily it could happen to anyone, even scrawny girls like me, whom nobody seemed to pay much attention to? Would that have made a difference? It seems unthinkable now. I heard so many warnings about countless other dangers growing up—AIDS, pot, failing in school, World War III, wearing too much makeup.

But maybe this one memory could’ve changed things between us. Or maybe it was doing that now.

I’ve often told myself there’s nothing much I need from my mother at this point other than childcare assistance and light conversation whenever we meet for lunch, so I’m surprised at the strength of my longing as I hold her hand and gaze into her eyes. There’s a spacious feeling in my chest, as if a window has burst open onto the darkest room of my heart. For the first time that I can remember in my adult life, I want her to be my mother—her and no one else. I’d give anything to be rocked back and forth in her arms as she hums an old folk song under her breath. And there’s a part of me that wants to do the same for her as well.

My own tears have begun their descent. My mom looks sheepish and guilty. She pulls her hand slowly out from between the tight envelope of my fingers.

I know it can’t be easy having a therapist for a daughter and never quite knowing how she’s perceiving you, or what she’s thinking about the things you’re telling her—or not telling her, for that matter. It’s probably a little like walking into an airport X-ray machine when you least expect it, or being vetted for a job you haven’t applied for and aren’t even sure you want.

She straightens, clears her throat, and gestures for the waiter to bring the check.

It dawns on me that I’m feeling something I’ve never actually felt toward her: unconditional love. It hurts, but it’s freeing. Maybe I’ve blamed her for things that are bigger than both of us. Maybe that’s the catch to being a woman in this world—a world full of men like my father and Brett Kavanaugh and overzealous journalists and artists like that one in the New York City studio. Maybe what my mother and I have always needed more than anything else—more than niceness and fancy meals—is to share this pain.

“We should probably get going,” she suggests abruptly.

I blow my nose into a tissue and stuff it into my pocket.

“You don’t want dessert?” I ask, glad to have my voice back.

She shakes her head and purses her lips in a weak smile.

By the time the waiter brings us the check, we’re chatting about the weather, again. I’m glad we’re keeping it light, the way it’s always been. It gives me a taste of the normalcy I need to reorient myself, locate my sunglasses, and remember where I parked my car. I take my mother’s small, frail elbow. As we walk out the door, I can feel her leaning into me, just a bit.

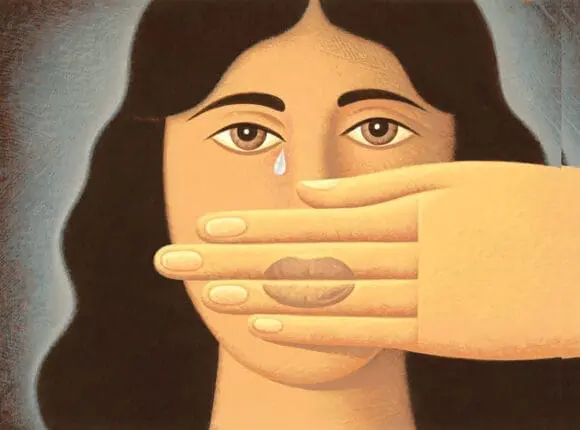

ILLUSTRATION BY ADAM NIKLEWICZ

Alicia Muñoz

Alicia Muñoz, LPC, is a certified couples therapist, and author of several books, including “Stop Overthinking Your Relationship” and “A Year of Us.” Over the past 18 years, she’s provided individual, group, and couples therapy in clinical settings, including Bellevue Hospital in New York, NY. Muñoz currently works as a senior writer at Psychotherapy Networker. Her latest book is “Happy Family: Transform Your Time Together in 15 Minutes a Day.“