Post-traumatic growth (PTG) is a hot topic in today’s therapy world, a catchall that many clinicians use to describe a client’s potential for resiliency after a traumatic event. I see this as a positive trend in a field that’s historically been focused on helping people cope with tragedy, instead of grow from it. But while PTG is a great concept, in our enthusiasm to help clients tap into their strengths and heal in a way that opens new doors for possibility, many of us forget how difficult—and therapeutic—it can be just to sit with their clients’ pain. After all, you can’t plant even the smallest seeds of PTG without being able to walk alongside clients in their darkest times, offer compassionate presence, and demonstrate patience and nonjudgment.

Having lost my husband to suicide, I’m particularly aware of how often therapists, despite their best intentions, get caught up in the “fixing” mentality and don’t work to acknowledge the pain that accompanies this type of traumatic loss. Even now, I can still drop into the moment when I round the staircase, walk into our bedroom, and find that my beloved husband had taken his life. Moments like these rearrange a person’s world. So when I sit with clients whose hearts are hemorrhaging in grief, whose core beliefs about life, God, and the world around them have all come into question, I want to offer more than a set of therapeutic tools to foster resiliency: I want to listen to their stories in a way that acknowledges that some things can never be fixed, and some pain will never go away.

Thankfully, no one has to have experienced the kind of existential shattering I did to be able to sit with clients who have—and to sow the seeds for PTG while understanding that the path to healing can be long and arduous. In a culture where suicide rates continue to rise, leaving loved ones devastated in the wake of each and every one, this understanding seems more important than ever. But as became clear with my client Jesse, while healing starts within the safe container of the therapeutic relationship, we can hold only so much before we need to remove the lid and help our clients use their own strengths to climb out.

The Weight of Guilt

When Jesse walked into my office, I saw a look of despair on her face that I’ve become all too familiar with. She’d come to see me after reading on my website that I’d lost my husband to suicide, as she had. She told me about the physical sickness she was experiencing every day under the weight of the loss and her belief that she was responsible for it.

Jesse was 55, still young to lose her lifelong partner. She’d met Matt in high school, and they’d built a good life together. They’d had their ups and downs, like any couple, but the three months before the suicide had been chaos. Matt had become severely depressed and increasingly paranoid. He talked often of taking his life, and Jesse desperately tried to get him to a treatment center, which he’d finally agreed to. The weekend before he was scheduled to go in, they’d traveled to Florida to visit friends. Matt had flown back early to tie up some loose ends at his job, and Jesse was to meet him a day later. Instead, she found his body in their shed, where he’d shot himself.

Jesse was drowning in the why questions. “Why didn’t we cancel the trip? Why didn’t I fly back with him that day?” she sobbed. “Why didn’t I say the right things on the phone the night before? Why couldn’t I save him? Why would he do this to us?” I knew these kinds of questions intimately, how they can bore into your soul like insidious parasites and leave you unable to function, let alone breathe. And yet, although Jesse was in agony, my job was to normalize this emotional experience for her.

Of course, nothing feels normal about a loss like this, but I looked into her eyes and said in a soft, slow voice to encourage regulation, “Jesse, I’m here, for as long as it takes. I want to help you take all the shattered pieces of your life and put them back together.” The enormity of her pain filled the room. “May I come sit next to you?” I asked. When she nodded, I sat beside her on the couch and told her, “Your nervous system is on overdrive right now. I’d like to show you how to take some breaths that will help calm you. Would that be okay?”

After we did a few rounds of slow breaths and she felt a little calmer, she said, “I’m not sure I believe it.”

“What don’t you believe?”

“That I can put my life back together.”

“Well, for now, let me believe it for you, okay?” I said. She nodded weakly. I then suggested we find a suicide support group for her to attend that week. Hearing her reluctance—”I don’t want to be around new people”—I told her why I’d found this kind of group so valuable when my husband died. “Suicide isn’t like a normal death,” I said. “This group will be full of people who’ve had similar experiences—which may help you feel less alone. And getting to know people who are farther along in their grief can give you hope that you’ll eventually get there too.”

I admitted to Jesse that I probably never would’ve gone to my group if a friend hadn’t taken me there. “Is it possible we could get someone you’re close with to go with you?” I asked. “I really believe you need more help than our weekly sessions can provide.”

I’m always honest with clients in this regard—therapy is an effective tool, but experiences like the one Jesse was going through often require more. This isn’t about lowering client expectations or exposing a therapist’s limitations: it’s about stating the reality, and every therapist, in my view, has an obligation to acknowledge it.

“I’m sure my sister would go with me,” Jesse said.

“I’d like to meet her and your other family members or friends who will be around you, if that’s possible. I want to show them some grounding techniques to use when you’re having post-traumatic flashbacks. People don’t always know how to offer support in that kind of situation.” She closed her eyes in pained recognition of this fact. “This will help,” I told her.

It’s a critical part of the work, especially in the early months, to build a secure network, where everyone is doing the same things to help stabilize the client’s traumatized brain.

Telling the Story of Loss

In our next session, although Jesse’s sister had taken her to a support group meeting, she reported feeling numb during and after it. She said she hadn’t spoken up at all, and wouldn’t have known what to say, even if she’d felt like it. To help her begin to express her pain, I showed her a picture of a shattered vase exploding into pieces. I often use it with clients who’ve experienced a traumatic loss because it gives them space to pause and find words or metaphors to describe what’s going on in their lives and bodies. If they can’t come up with anything, I invite them to be curious about what the numbness is trying to tell them.

When I showed Jesse the shattered vase, she stared at the image for a while, then slowly found words for what she was feeling: “A bomb has gone off in my life and everything is in ruins. He should have killed me too!”

“I’m here with you,” I said simply as she sobbed.

A loss like Jesse’s can profoundly disrupt one’s taken-for-granted constructions about life. Eventually, I wanted to help Jesse interrogate the tacit assumptions that were challenged by the trauma, while helping her grope her way toward new sustaining frameworks of meaning. I wanted to help her move to a place of acceptance, while still holding the pain. At this stage, however, I just wanted to let her know that she wasn’t alone, and that I’d sit with her as long as was necessary, no matter how intense her feelings were.

The following week, Jesse said the last support group meeting she’d attended “might’ve” been worthwhile. “It was good to hear other people’s stories,” she conceded. At this point, I suggested we could start to look at her own story, taking into account the inner qualities and external resources that have helped her face major losses in the past.

“Jesse, it’s often useful to develop a Loss Timeline in therapy,” I told her. This is a technique borrowed from narrative therapy. “Believe it or not, looking at the past tragedies in your life will help us get a better sense of what we can do to help you now. We can work on it together.”

“Okay, well,” she started, taking in a breath, “my mom died after a battle with cancer. I was only 32. Then my dad got sick about 10 years later. He lived with us for a long time until he passed away, and Matt was very close to him. We both took care of him.” She went on to tell me about losing six friends in one year, and about a cousin who’d been struck by lightning in a parasailing accident; she’d visited him in the hospital every day for weeks.

Through her storytelling, it became clear that although her husband’s suicide was the most tragic event of her life, Jesse was no stranger to significant loss. But her tenacity and perseverance shone through as she recalled the challenge of moving through grief in the past, only to be confronted with yet another loss. “How on earth did you get through all this?” I asked, genuinely awestruck.

“I don’t know,” she answered. “I’ve never thought of myself as very strong.”

“Well, you are strong,” I said, “and I’d like you to start noticing how this strength shows up in even the smallest ways in your life each day moving forward.”

In the early stages of traumatic loss, survivors aren’t coming to therapy to experience growth, so I wasn’t surprised that Jesse didn’t engage with the idea right away. “I can’t notice anything but Matt’s clothes still in the closet, the food he liked in the cupboards. I just want him back!” she cried. She wasn’t interested in exploring new possibilities, but I couldn’t help her make a shift unless her mind could do just that. So planting a seed as gently as possible, I simply asked her to be curious about her life whenever it was appropriate.

More than a month later, she came in smiling. “I was thinking about what you said,” she began, “about my persevering through so much. A friend told me this week that I was the strongest person she’s ever known. It really hit me. I started to consider that maybe I am strong, even without Matt. I began journaling about my losses, like you suggested, and I realized I’ve survived it all, and I’m still standing.” We’d made a huge shift.

“Jesse, how would you like your life to look a year from now?” I asked in a subsequent session.

“I think I want to be doing something that helps me live my life again and honors Matt at the same time,” she answered. I knew then that one of the seeds I’d been carefully planting may have started to send out a single, fragile root.

Making Meaning and Taking Risks

Survivors of traumatic loss don’t need solutions. They don’t need fixing. This kind of pain needs presence and patience while we do the slow work of planting seeds for healing and growth. And when they’re ready, as Jesse was now, the most important aspect of treatment is to explore the meaning they’ve attached to the trauma. For Jesse, it was the all-consuming belief that she was responsible for her husband’s suicide, that she should never have let him fly home alone. Along with her belief that she couldn’t live without Matt, it was keeping her stuck.

The beginning phase of this work wasn’t to convince her that she wasn’t guilty, but to honor the part of her that believed she was. I allowed her the time and space to give that part of her a voice. Then one day I planted another seed: “Jesse, is it possible that Matt’s suicide wasn’t your fault?” I asked. Before she answered, I invited her just to sit with that possibility, to see what came up in her body.

She sat quietly. “I guess it’s possible,” she said after a while.

“What would it mean if you could hold on to the idea that there was nothing you could’ve done to stop Matt from taking his life?” I asked.

Almost in a whisper she responded, “That I could live.”

Using Martin Seligman’s concept of explanatory styles, I showed Jesse that her taking responsibility for Matt’s suicide meant she was taking a “me, only me” perspective. Gently, I asked her what she thought Matt’s responsibility might have been in all this?

“Well, one social worker we met with told him he needed to take some responsibility for his care. He needed to take the medication he was prescribed and get treatment.”

“Did he do those things?” I asked.

“No,” she said quietly.

After that session, I felt she’d made another shift. And what she needed now was to experience a different reality apart from the hell she was living in. How did I help make that happen? By encouraging her to risk.

Jesse needed more than an intellectual knowing that life could be different, or even better, than it had since the event: she needed an experience of knowing. In the beginning, the risks I suggested were very small things, like starting to work out again. After a while, she reported that her friend was coming over to work out with her twice a week.

“Great,” I said. “How about trying yoga? A lot of research shows the benefits for people who’ve experienced trauma.” She said there was a studio by her house, but she wanted to start with some online videos she’d seen. I was pleased she was willing to try. As time went on, she was able to take bigger risks. Two years later, she actually went on a few dates. Each new experience was enlarging her world. The grief never got smaller; her world just got a little bigger.

Fostering Self-Compassion

Jesse’s move toward PTG didn’t mean the pain or guilt disappeared. In fact, there were many times when she still told me things like “I might as well have pulled the trigger” and “I should never have left him alone.” I sat with her in her pain during these moments, offering her presence without any judgment. I didn’t try to silence the part that felt responsible. Instead, an important aspect of the work was inviting her to practice being kind, gentle, and patient with herself, to develop the compassionate part of her that I’d come to know.

By this juncture, Jesse and I had explored the effects of her cognitive distortions and toxic thinking, and she was increasingly able to bring mindful attention to the machinations of her internal monologues. But fostering self-compassion is a challenge for many clients, especially women. We tend to see it as self-pity or self-centeredness. And it’s often the most difficult part of the process for clients to consider changing the way they relate to themselves. When Jesse came in one afternoon and repeated, “I wasn’t a good enough wife; I should have . . .” I stopped her.

“Jesse,” I said, “I wonder if you can say this to yourself in a way that doesn’t bring up so much guilt, a way that’s kinder and will help you move forward. Would you be willing to give it a try?”

She got it. “What I’m telling myself is becoming a self-defeating story. It only makes me feel worse. It won’t bring him back. The truth is, I did the best I could with what was happening and with his erratic behavior.” She looked me directly in the eyes.

“Jesse,” I said, “What you just did was beautiful, calling to mind how you did care for your husband. You loved him until he took his last breath and beyond. Can you remember his words to you about his gratitude for your love and support?”

“Yes,” she said, “I’m going to choose to set my mind on those truths and practice self-kindness. I’m coming to realize that letting go of my guilt doesn’t mean I’m letting go of him.”

What does it mean to experience post-traumatic growth? With Jesse, I think it was marked by a few things. For starters, she became able to release herself from the responsibility for the tragedy. And she was eventually able to recognize that not only had she survived it, but she had the capacity to move forward and create a meaningful life for herself. Notably, she was also able to honor the help she was receiving from others who were walking alongside her, including the members of the support group.

One afternoon Jesse surprised me by announcing, “I want to use my strengths to help others. I’m strong enough for that now.”

“You’re a warrior, Jesse,” I said, and meant it.

Our losses aren’t the end of the story; they’re only the beginning. Jesse is now offering support to others in her group. I still see her on occasion, but as a fellow sojourner through the dark night of the soul, I know she’s come out from behind the shadow of loss and embraced life once again.

Case Commentary

By Douglas Flemons

Suicide is a violent act, and suicide survivors—the loved ones and close friends who must live in the aftermath—suffer a crushing grief, complicated by second-guessing, unanswerable questions, and crippling guilt. In this case study, Rita Schulte offers a master class in how to meet a devasted survivor in his or her bottomless pain and how to deftly help without undertaking misguided rescue attempts that would inadvertently subject the person to further violence.

Herself a suicide survivor, Schulte has distilled and transmuted this experience into a resourceful way of thinking and working. She holds a soft candle to light the way for her client, Jesse, not a blazing searchlight to shine in her eyes. She is present. She is respectful and kind. She is patient and trustworthy, promising to be available for “as long as it takes.”

The small, deft touches stand out as she underscores the importance of “just sitting” with suicide survivors. And with a hard-won sensitivity to their existential isolation, she isn’t content to sit across from Jesse: she gets up from her chair and walks over to sit beside her. Unlike her client, Schulte isn’t frozen, and she knows what to do: she lets Jesse know that she isn’t alone. And then she puts this assertion into motion as well, ensuring that Jesse gets hooked up with a support group, with a community.

Schulte has a clear map guiding her. She offers to show Jesse a way of breathing that will help her calm down, and she proposes to show friends and family members the best way to offer their support. She encourages Jesse to try yoga, to start working out, to take emotional risks. Therapists who presume to know what clients should do can end up at loggerheads with them when the clients dig their heels in against all the good advice. Schulte mostly avoids such a dynamic by balancing her confident belief about what’s best with a tentative way of proposing ideas and suggestions. She consistently asks permission to proceed.

There’s one part of the case that troubles me. After sufficient time has passed, Schulte floats a question about Jesse’s husband, Matt, wondering aloud whether it’s possible that his suicide wasn’t Jesse’s fault. This is part of Schulte’s sensible effort to introduce the notion that Matt bore responsibility for his own choices. But then comes this: “What would it mean,” she asks, “if you could hold on to the idea that there was nothing you could’ve done to stop Matt from taking his life?”

I see a danger in proposing such a belief as a solution for survivors’ guilt, and doing so didn’t work in this case, anyway: at the end of the therapy, Jesse is still lamenting that she left him alone. If we promote the myth that nothing can be done to prevent the suicide of people intent on killing themselves, then we may miss countless opportunities for crucial and effective intervention. The fact is, as Thomas Joiner states in Myths about Suicide, the vast majority of suicidal individuals are ambivalent about dying, and timely outreach saves lives.

But what about the guilt of grieving survivors? Schulte also pursues an alternative approach to addressing Jesse’s guilt, one aimed not at making the grief smaller, but at helping “her world [get] a little bigger.” And she does this by inviting Jesse to treat herself with the kindness, gentleness, and patience that Schulte has been offering from the beginning. This opens a pathway for Jesse to become as wise and resourceful for others as Schulte has been for her.

Want to earn CE hours for reading this? Take the Networker CE Quiz.

ILLUSTRATION BY SALLY WERN COMPORT

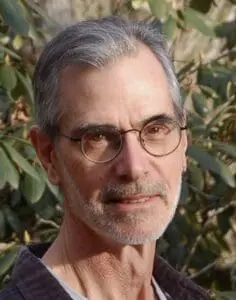

Rita Schulte

Rita A. Schulte, LPC, specializes in the treatment of depression, suicidality, and grief. Rita is no stranger to loss and suffering, having lost her beloved husband to suicide in 2013. In addition to her private practice, Rita is the creator and host of Heartline Radio where she talks with counselors, authors and everyday people about moving through the difficulties of life. Rita writes for numerous publications and blogs and her articles have appeared in Counseling Today Magazine, Thriving Family, Kyria and LifeHack.org. Learn more about Rita on her website.

Douglas Flemons

Douglas Flemons, PhD, LMFT, lives and maintains a telehealth practice in Asheville, North Carolina. Professor Emeritus of Family Therapy at Nova Southeastern University, he’s coauthor of Relational Suicide Assessment, coeditor of Quickies: The Handbook of Brief Sex Therapy, and author, most recently, of The Heart and Mind of Hypnotherapy.