“I don’t think I want to live if I have to go on feeling like this.” I hear this remark all too often from anxiety sufferers. They say it matter-of-factly or dramatically, but they all feel the same way: if anxiety symptoms are going to rule their lives, then their lives don’t seem worth living.

What is it about anxiety that’s so horrific that otherwise high-functioning people are frantic to escape it? The sensations of doom or dread or panic felt by sufferers are truly overwhelming–the very same sensations, in fact, that a person would feel if the worst really were happening. Too often, these, literally, dread-full, sickening sensations drive clients to the instant relief of medication, which is readily available and considered by many insurance companies to be the first line of treatment. And what good doctor would suggest skipping the meds when a suffering patient can get symptomatic relief quickly?

But what clients don’t know when they start taking meds is the unacknowledged cost of relying solely on pills: they’ll never learn some basic methods that can control or eliminate their symptoms without meds. They never develop the tools for managing the anxiety that, in all likelihood, will turn up again whenever they feel undue stress or go through significant life changes. What they should be told is that the right psychotherapy, which teaches them to control their own anxiety, will offer relief from anxiety in a matter of weeks–about the same amount of time it takes for an SSRI to become effective.

Of course, therapists know that eliminating symptomatology isn’t the same as eliminating etiology. Underlying psychological causes or triggers for anxiety, such as those stemming from trauma, aren’t the target of management techniques; they require longer-term psychotherapy. However, anxiety-management techniques can offer relief, and offer it very speedily.

The unpleasant symptoms most likely to be helped by medication are the very ones that the 10 best-ever anxiety-management techniques are intended to correct. They fall into three typical clusters:

– the physical arousal that constitutes the terror of panic;

– the “wired” feelings of tension that correlate with being “stressed out” and can include pit-of-the-stomach doom;

– the mental anguish of rumination–a brain that won’t stop thinking distressing thoughts.

A therapist armed with methods for addressing these clusters can offer her anxious client the promise of relief for a lifetime, if she knows which of these “10 best” techniques work for which symptoms, and how to use them.

Cluster One: Distressing Physical Arousal

Panic is the physical arousal that sends many clients running for Xanax. Sympathetic arousal causes the heart-thumping, pulse-racing, dizzy, tingly, shortness-of-breath physical symptoms that can come from out of the blue, and are intolerable when not understood. Even high levels of acute anxiety that aren’t as intense as outright panic attacks can constitute very painful states of arousal. Physical symptoms of anxiety include constant heightened physical tension in the jaw, neck, and back, as well as an emotional-somatic feeling of doom or dread in the pit of the stomach. The feeling of doom will always set off a mental search for what might be causing it.

Bad as these symptoms are, there are methods that, when followed regularly as lifelong habits, offer tremendous relief.

Method 1: Manage the Body.

Telling anxiety-prone clients to take care of their bodies by eating right, avoiding alcohol, nicotine, sugar, and caffeine, and exercising is a strikingly ordinary “prescription,” but not doing these things can undermine the effectiveness of other antianxiety techniques. During the summer before Ellie went off to college, for example, she’d almost eliminated her anxiety by practicing deep, calm breathing and learning to stop her catastrophic thinking. She’d even been able to stop taking the antianxiety medication she’d used for years. But two months after starting college, her panic attacks came roaring back with a vengeance. She came back to see me, but quickly let me know that she was going to call her psychiatrist for another Xanax prescription. I suggested that, before she made the call, she spend a couple of weeks keeping a “panic profile”–a journal recording when and under what circumstances she suffered from panic attacks.

A couple of weeks later, she came to my office smiling broadly. “I figured it out,” she said, grinning as she showed me her panic profile. She’d traced her panic attacks to days after she drank heavily and smoked cigarettes–neither of which had she done over the summer while living in her parents’ house. Also, her caffeine use had risen dramatically while at school–to help her wake up for classes after partying at night–and her diet had devolved to pizza and doughnuts. She really didn’t want to give up these habits, but keeping the journal had reminded her that her anxiety symptoms are physical, and that calming her body had defused her panic triggers once before. Taking care again to eliminate CATS (caffeine, alcohol, tobacco, sugar + Nutrasweet), Ellie got back on track without returning to meds. The simple rule–manage the body–must remain a first priority throughout treatment for anxiety. Ellie had a major relapse when she let go of routine self-care.

Therapists who remember that humans have bodies as well as minds are much likelier to inquire routinely about ongoing self-care, including sleep and exercise. They’re also more willing to help clients overcome their reluctance to follow a self-care routine. A tip to remember for female clients who experience a resurgence of symptoms in spite of the fact that they’re managing their body is to consider hormonal changes. Pregnancy, postpartum changes, hysterectomy, and interruptions in cycles may contribute to anxiety. The slow process of menopause, which may begin over a wide range of ages, is another factor to consider. Shifts in thyroid function also contribute to shifts in anxiety. They can occur at any age, and predominate in female clients. Therapists need to be particularly alert to what might be going on in the body when a client who was previously doing well starts having trouble.

Method 2: Breathe.

Ellie and I next reviewed her use of diaphragmatic breathing to ward off the panic. As it turned out, she’d forgotten how helpful breathing had been when we first started working together, and had quit doing it. Now, not only did she suffer again from panic, but she thought it was too powerful to be relieved merely by breathing deeply. She’d begun to panic just thinking about feeling panic. I’ve often found that when clients say that breathing “doesn’t work,” it’s because they haven’t learned to do it correctly. Or once having learned it, they’ve given it up when they felt better, believing that they no longer needed to do it. By the time they feel anxiety returning, they’re convinced that something so simple can’t possibly be really effective. Therefore, it’s important for therapists to emphasize and reemphasize that breathing will slow down or stop the stress response, if the client will just do it.

The biggest block to making breathing truly helpful is the time it takes to practice it until it becomes an ingrained habit. Most relaxation books teach clients to practice breathing once a day for 10 minutes, but I’ve never found a client who actually learned how to do it from this one, daily, concentrated dose. I don’t teach clients to breathe for lengthy periods until they’ve practiced it for very short periods many times a day. I ask them to do the conscious, deep breathing for about one minute at a time, 10 to 15 times per day, every time they find themselves waiting for something–the water to boil, the phone to ring, their doctor’s appointment, the line to move at the bank. This will eventually help them associate breathing with all of their surroundings and activities. This way, they’re more likely to actually remember to breathe when anxiety spikes. Ellie needed a review session in breathing to help her get back on track.

Method 3: Mindful Awareness.

Since the return of her panic attacks, Ellie had also begun to fear that she’d always be afraid. “After all,” she said, “I thought I was cured when I went back to school, and now look at me! I’m constantly worried I’ll have another panic attack.” She’d started to give catastrophic interpretations to every small, physical sensation–essentially creating panic out of ephemeral and unimportant changes in her physical state. A slight chill or a momentary flutter in her stomach was all she needed to start hyperventilating in fear that panic was on its way, which, of course, brought it on. She needed to stop the catastrophic thinking and divert her attention away from her body.

Like most anxious people when they worry, Ellie was thinking about the future and wasn’t in the moment. She felt controlled by her body, which required her to be on the lookout for signs of panic. She’d never considered that she could manage her body–and prevent panic–by controlling what she did or didn’t pay attention to. But, in fact, by changing her focus, she could diminish the likelihood of another panic attack. A wonderful technique, this simple “mindful awareness” exercise has two simple steps, repeated several times.

1. Clients close their eyes and breathe, noticing the body, how the intake of air feels, how the heart beats, what sensations they have in the gut, etc.

2. With their eyes still closed, clients purposefully shift their awareness away from their bodies to everything they can hear or smell or feel through their skin.

By shifting awareness back and forth several times between what’s going on in their bodies and what’s going on around them, clients learn in a physical way that they can control what aspects of their world–internal or external–they’ll notice. This gives them an internal locus of control, showing them, as Ellie learned, that when they can ignore physical sensations, they can stop making the catastrophic interpretations that actually bring on panic or worry. It’s a simple technique, which allows them to feel more in control as they stay mindful of the present.

Cluster Two: Tension, Stress, and Dread

Many clients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) experience high levels of tension that are physically uncomfortable and compel them to search frantically for the reasons behind their anxiety. They hope they can “solve” whatever problem seems to be causing anxiety and thus relieve its symptoms. But since much of their heightened tension isn’t about a real problem, they simply waste time running around their inner maze of self-perpetuating worry. And even if their tension does stem from psychological or neurobiological causes, there are ways to eliminate the symptoms of chronic worry before addressing those dimensions. The following methods are most helpful for diminishing chronic tension.

Method 4: Don’t Listen When Worry Calls Your Name.

Colleen feared I’d think she was crazy when she said, “It’s as if my anxiety has a voice. It calls to me, ‘Worry now,’ even when there’s nothing on my mind. Then I have to go looking for what’s wrong.” And she was very good at finding something wrong to worry about. An executive who had a lot of irons in the fire, she had no shortage of projects that needed her supervision. On any day, she could worry about whether a report had been correct, or projected figures were accurate, or a contract would generate income for her firm. In describing the voice of worry, she was describing that physical, pit-of-the-stomach sense of doom that comes on for no reason, and then compels an explanation for why it’s there. This feeling of dread and tension, experienced by most GAD clients, actually comprises a state of low-grade fear, which can also cause other physical symptoms, like headache, temporo-mandibular joint (TMJ) pain, and ulcers.

Few realize that the feeling of dread is just the emotional manifestation of physical tension. This “Don’t Listen” method decreases this tension by combining a decision to ignore the voice of worry with a cue for the relaxation state. Early in treatment, GAD clients learn progressive muscle relaxation to get relief. I always teach them how to cue up relaxation several times throughout the day by drawing a breath and remembering how they feel at the end of the relaxation exercise. We usually pair that deeply relaxed state with a color, image, and word to strengthen associations with muscle relaxation and make it easier to cue the sensation at will.

We then use that ability to relax to counteract the voice of worry. Clients must first learn that worry is a habit with a neurobiological underpinning. Even when a person isn’t particularly worried about anything, an anxiety-prone brain can create a sense of doom, which then causes hypervigilance as the person tries to figure out what’s wrong. Colleen smiled with recognition when I said that, when she was in this state, it was as though her brain had gone into radar mode, scanning her horizons for problems to defend against. I asked her to pay attention to the order of events, and she quickly recognized that the dread occurred before she consciously had a worry. “But,” she announced, “I always find something that could be causing the doom, so I guess I had a good reason to worry without realizing it.”

She believed the doom/dread must have a legitimate cause, and was relieved to learn that her need to find the cause (when there really wasn’t one) stemmed from a brain function. This cause-seeking part of her brain, triggered by changes in her physiology that made her feel dread, in effect, called out, “Worry now!”

To stop listening to that command to worry, I suggested that she say to herself, “It’s just my anxious brain firing wrong.” This would be the cue for her to begin relaxation breathing, which would stop the physical sensations of dread that trigger the radar.

Method 5: Knowing, Not Showing, Anger.

Anger can be so anxiety-provoking that a client may not allow himself to know he’s angry. I often find that clients with GAD have an undetected fear of being angry. Bob was a case in point. He had such a tight grin that his smile was nearly a grimace, and his headaches, tight face muscles, and chronic TMJ problems all suggested he was biting back words that could get him into trouble. There were many arenas of his life in which he felt burdened, such as losing out on a promotion and his wife’s chronic inability to spend within their budget, but he genuinely believed he was “putting a good face” on his problems. As with other anxious clients, the acute anxiety was compelling enough to command the therapy time, and it would have been possible to ignore the anger connection. However, as long as anger stays untreated, the anxious client’s symptoms will stay in place.

When a client fears anger because of past experience–when she remembers the terrifying rage of a parent, or was severely condemned for showing any anger herself–the very feeling of anger, even though it remains unconscious, can produce anxiety. The key to relieving this kind of anxiety is to decrease the client’s sense of tension and stress, while raising the consciousness of anger so that it can be dealt with in therapy. I’ve found that simply being able to feel and admit to anger in sessions, and to begin working on how to safely express it, diminishes anxiety. I tell clients, “To know you’re angry doesn’t require you to show you’re angry.”

The technique is simple. I instruct clients that the next time they’re stricken with anxiety, they should immediately sit down and write as many answers as possible to this specific question, “If I were angry, what might I be angry about?” I tell them to restrict their answers to single words or brief phrases. The hypothetical nature of the question is a key feature, because it doesn’t make them feel committed to the idea that they’re angry. They may destroy the list or bring it in for discussion, but I ask them to at least tell me their reactions to writing this list. Without fail, this exercise has helped some of my anxious clients begin to get insight into the connection between their anger and their anxiety, which opens the door to deeper levels of psychotherapy that can resolve long-standing anger issues.

Method 6: Have a Little Fun.

Laughing is a great way to increase good feelings and discharge tension. The problem for anxious clients is that they take life so seriously that they stop creating fun in their lives, and they stop experiencing life’s humorous moments. Everything becomes a potential problem, rather than a way to feel joy or delight.

Margaret was a witty woman, whose humor was self-deprecating. A high-level executive who typically worked 12- to 14-hour days, she’d stopped laughing or planning fun weekends about two promotions back. Her husband rarely saw her on weeknights, and on Saturday and Sunday, she typically told him she was just “going to run over to the office for a little while”–anywhere from 3 to 7 hours. When I asked her to make a list of what she did for fun, she was stymied. Other than having a drink with friends after work, her list of enjoyable activities was almost nonexistent.

Getting in touch with fun and play isn’t easy for the serious, tense worrier. I’ve often found, however, that playing with a child will get a person laughing, so I asked her to spend some time with her young nieces. She agreed, and noticed that she felt more relaxed after being with them for an afternoon. Then I asked her to watch for any impulse to do something “just because,” without any particular agenda in mind. When I saw her next, she seemed transformed. She said, “I had an impulse to stop for an ice-cream cone, so I just went out and got it. I don’t know when the last time was that I felt like doing something and just did it–no worries about whether everyone else had a cone or whether I should wait till later. It was fun!” Over time, listening to her inner wishes helped Margaret feel that there was a reservoir of pleasure in life that she’d been denying herself, and she began to experiment with giving herself the time to find it.

But Margaret needed to rediscover what she liked after years of ignoring pleasure. For a time, our therapy goal was simply to relearn what she had fun doing. Fun-starved clients sometimes need a “prescription,” like “Take two hours of comedy club and mix with a special friend, once a week” or “Plan one weekend out of town with your husband every two months.” Not surprisingly, tightly wired workaholics initially need to make fun a serious goal of treatment, something to be pursued with some of the same doggedness they put into work. But once they actually find themselves laughing and enjoying themselves, they become less tightly wired, less dogged, and more carefree. Laughter itself is one of the best “medications” of all for tension and anxiety.

Cluster Three: The Mental Anguish of Rumination

The final methods are those that deal with the difficult problem of a brain that won’t stop thinking about distressing thoughts. Worries predominate in social phobia, GAD, and other kinds of anxiety, and continual rumination can create nausea and tension, destroying every good thing in life. A metaphor drawn from nature for this kind of worry would be kudzu, the nearly unkillable plant that proliferates wildly, suffocating every other form of life, just as continual worry suffocates clients’ mental and emotional lives.

I don’t believe rumination is caused by deep-seated conflict in the way anger-anxiety might be; I think it’s almost entirely a neurobiologically driven feature of anxiety. What clients usually worry about–often ordinary, day-to-day concerns–is less important than the omnipresence of the worry. Their brains keep the worry humming along in the background, generating tension or sick feelings, destroying concentration, and diminishing the capacity to pay attention to the good things in life. Seeking reassurance or trying to solve the problem they’re worrying about becomes their sole mental activity, obscuring the landscape of their lives. Nor can ruminators ever get enough reassurance to stop worrying altogether. If one worry is resolved, another pops right up–there’s always a fresh “worry du jour.”

Therapy with these clients shouldn’t focus on any specific worry, but rather on the act of worrying itself. If a ruminating brain is like an engine stuck in gear and overheating, then slowing or stopping it gives it a chance to cool off. The more rumination is interrupted, the less likely it’ll be to continue. The following methods are the most effective in eliminating rumination.

Method 7: Turning It Off.

Peter’s rumination was the bane of his existence. A mile-a-minute supersalesman with remarkable drive, he had a capacity to fret that could wear out a less energetic person. His mind traveled from one possible problem to another like a pinball that never comes to rest. Ruminating worry preoccupied him so much that he couldn’t enjoy being with his children or relax before going to sleep–his last conscious awareness at night was of worry.

In therapy, he had a hard time focusing on just one issue at a time; one worry just reminded him of another and another after that. Before addressing the psychological underpinnings of worry in his life, we needed to find a way for Peter to cool down his brain and halt the steady flow of rumination for a while.

From Eugene Gendlin’s Focusing method, I’ve borrowed the concept of “clearing space” to turn off and quiet the ruminative mind. I ask the client to sit quietly with eyes closed and focus on an image of an open container ready to receive every issue on his or her mind. She’s then instructed to see and name each issue or worry, and imagine putting it into the container. When no more issues come to mind, I suggest that the client mentally “put a lid” on the container and place it on a shelf or in some other out of the way place until she needs to go back to get something from it. Once the jar is on the shelf, the client invites into the space left in her mind whatever is the most important current thought or feeling. Perhaps she’s at the office and needs to think about a work-related issue, or she needs to shop and should plan what she’ll buy, or she’s with friends and wants to focus on what they’re saying. At night, right before sleep, the client is asked to invite a peaceful thought to focus on while drifting off.

Peter is a man who prefers tangible tools to metaphorical ones, so when he was at home, I suggested that instead of using imagery, he make a written list of the issues he couldn’t turn off and put the list in a desk drawer to wait for him overnight, or even place it in his freezer to help him “chill out.” Any tangible technique is fine, such as Al Anon’s idea of a “God Box” to hold slips of paper, each with a worry written down that the client is turning over to God. The goal of “turning it off” is to give the ruminative mind a chance to rest and calm down.

Method 8: Persistent Interruption of Rumination.

Ruminative worry has a life of its own, consistently interfering with every other thought in your client’s mind. Thought-stopping/ thought-replacing is the most effective cognitive-therapy technique for interrupting chronic rumination, but I find the key to making it work is persistence . Clients very quickly pick up on the technique itself, but they’re always shocked by how rumination can subvert all their good efforts, and by how persistently they have to keep at it to succeed. I’ve had clients come back and say the technique didn’t work, because they’d tried it 20 to 30 times in a day and they still were ruminating. I tell them that they must do it every time they catch themselves ruminating, even if it is 1,000 times a day or more! That’s what I mean by persistence.

Darla is a good example. She was a self-described worrywart before she got cancer, but after her diagnosis, her anxiety zoomed out of control. Although treatment was successful and she’d been in remission for some time, she still had constant, negative, racing thoughts about whether her cancer would recur. A really hard worker in therapy, she did every method I suggested, and was ready to use thought-stopping to interrupt her ruminations about cancer. “Remember,” I told her, “winning this game is about persistence. Do the thought-stopping exercise every single time you find yourself worrying, no matter how many times you have to do it.”

At the next session, she reported her success–she really had radically cut back the amount of worrying she was doing. But it worked only because I’d warned her about how persistent she’d have to be. “When you told me I’d have to thought-stop every time, even if it was 1,000 times a day,” she said, “I thought you were kidding. If you hadn’t warned me, I’d have given up in despair after about 100 times, thinking it would never work for me. Since you said 1,000, I figured I’d better stay the course. After a couple of days, it got markedly better.” Rumination is persistent, and the only way to beat it at its own game, so to speak, is to be even more persistent.

Method 9: Worry Well, But Only Once.

Some worries just have to be faced head-on, and worrying about them the right way can help eliminate secondary, unnecessary worrying. Connie knew that her next medical results were going to tell the story of whether she needed surgery. Although there’s always a level of legitimate worry about any medical problem, some medical conditions, like high thyroid, create anxiety symptomatology. Connie’s medical problems weren’t causing the anxiety symptoms, but her anxiety about her condition was getting in the way of her medical recovery. She called the doctor’s office repeatedly, until the doctor said she’d fire Connie if she got one more phone call before the test results came in.

Connie was out of control with worry, so we tried out a method that actually had her worry, but worry well–and only once. Here’s how that works. The client must: (1) worry through all the issues; (2) do anything that must be done at the present time; (3) set a time when it’ll be necessary to think about the worry again; (4) write that time on a calendar; and (5) whenever the thought pops up again, say, “Stop! I already worried!” and divert her thoughts as quickly as possible to another activity.

Connie and I set a 10-minute time limit on our worry session, and then together thought through all the possible ramifications of a positive test result. She covered things such as “Who’ll watch the cat while I’m in the hospital?” “Will I have to miss too many days of work?” “Will I need a ride home?” We covered everything from the mundane to the serious, if unlikely, “What if I die while in surgery?”

It’s critical to this method to cover all the bases, but 10 minutes, surprisingly, is an adequate amount of time in which to do that. At the end of the worry period, Connie agreed that she had no other worries related to the surgery, so we set a time at which she thought she’d need to think about the problem again. We agreed that the next time she should let the possibility of surgery cross her mind was when the doctor’s office called. Until that moment, any thought would be counterproductive. She wrote in her PDA that she could worry again at 4 p.m. on Tuesday afternoon, by which time the results would be in and the doctor had promised to call. If she hadn’t heard at that point, then she could start worrying and call the doctor’s office.

Having worried well, we moved to the “Only Once” part of the method. She then practiced, “Stop It! I already worried!” and we made a list she could carry around with her that enumerated some distractions to use. While this may sound trite, her brain believed her when she said she’d already worried, because it was true.

Method 10: Learn to Plan Instead of Worry.

A big difference between planning and worrying is that a good plan doesn’t need constant review. An anxious brain, however, will reconsider a plan over and over to be sure it’s the right plan. This is all just ruminating worry disguising itself as making a plan.

Clients who ruminate about a worry always try to get rid of it by seeking the reassurance that it’s unfounded. They believe that if they get the right kind of solution to their problem–the right piece of information or the best reassurance–they’ll then be rid of the worry once and for all. They want to be absolutely sure, for example, that a minor mistake they made at work won’t result in their being fired. In reality, however, a ruminating brain will simply find some flaw in the most fail-safe reassurance and set the client off on the track of seeking an even better one.

One good way to get out of the reassurance trap is to use the fundamentals of planning. This simple but often overlooked skill can make a big difference in calming a ruminative mind. I teach people how to replace worrying with planning. For most, this includes: (1) concretely identifying a problem; (2) listing the problem-solving options; (3) picking one of the options; and (4) writing out a plan of action. To be successful with this approach, clients must also have learned to apply the thought-stopping/thought-replacing tools, or they’ll turn planning into endless cycles of replanning.

After they make a plan, ruminating clients will feel better for a few minutes and then start “reviewing the plan”–a standard mental trick of their anxiety disorder. The rumination makes them feel overwhelmed, which triggers their desire for reassurance. But when they’ve actually made the plan, they can use the fact that they have the plan as a concrete reassurance to prevent the round-robin of ruminative replanning. The plan becomes part of the thought-stopping statement, “Stop! I have a plan!” It also helps stop endless reassurance-seeking, because it provides written solutions even to problems the ruminator considered hopelessly complex.

For example, if Connie, who’d worried well about surgery, found out she did have to have the surgery, she could write out the plan to get ready. The new plan would cover all the issues she’d identified in her worry session, from finding a catsitter to writing a living will. She’d put completion dates in for each step and cross off the items as she did them until the day of the surgery. Then, each time she needed reassurance, the concrete evidence that she had a good plan would enable her to go on to some other thought or activity.

While these techniques aren’t complicated or technically difficult to teach, they do require patience and determination from both therapist and client. For best results, they also demand clinical knowledge of how and why they work, and with what sorts of issues; they can’t simply be used as all-purpose applications, good for anybody in any circumstance.

But the rewards of teaching people how to use these deceptively simple, undramatic, and ungimmicky methods are great. While clients in this culture have been indoctrinated to want and expect instantaneous relief from their discomfort at the pop of a pill, we can show them we have something better to offer. We can give people a lasting sense of their own power and competence by helping them learn to work actively with their own symptoms, to conquer anxiety through their own efforts–and do this in a nonmanipulative, respectful, engaging way. People like learning that they have some control over their feelings; it gives them more self-confidence to know they’re not the slaves of physiological arousal or runaway mental patterns. And what we teach them is like playing the piano or riding a bicycle: they own it for life; it becomes a part of their human repertoire. What medication can make that claim?

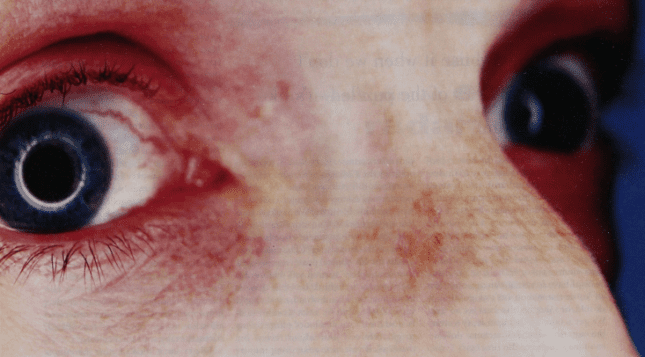

Photo by Getty Images / Moritz Steiger

This article first appeared in the September/October 2005 issue.

Margaret Wehrenberg

Margaret Wehrenberg, PsyD, is a clinical psychologist, author, and international trainer. Margaret blogs on depression and anxiety for Psychology Today. She has written nine books on the topic of managing anxiety depression, and her most recent book is Pandemic Anxiety: Fear. Stress, and Loss in Traumatic Times.