Much of this issue is devoted to exploring a big-picture question seemingly removed from the small dramas that take place in our offices every day: what might therapists contribute to understanding and healing the intense political polarization going on all around us? Along the way, we came across an unusually prescient article by longtime contributor Michael Ventura that still offers a provocative perspective on our current cultural ferment. We’ve republished it here in the belief that, in some ways, it seems even more relevant today than when it first appeared, almost 10 years ago.

Watch documentary footage of the 1960 Democratic convention, which nominated John F. Kennedy—remembering that in 1960 many were troubled deeply that the Oval Office could be the prize of an upstart, rich, Catholic Irish American. Scan the 1960 convention floor: there are no women. Well, I didn’t use a magnifying glass; there might be half a dozen, so amend that to read: there are nearly no women, and certainly no women with speaking parts (as Hollywood would say). The California and New York delegations may have harbored the odd Chinese or Japanese American, and the rare Jew (also with no speaking parts), but the 1960 Democratic convention was overwhelmingly WASP.

As for African Americans, only two had speaking parts: the Congressman from Harlem, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., and the entertainer Sammy Davis, Jr. When Davis took the stage to sing “God Bless America” with Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, entire delegations of Southern Democrats walked out in protest—they didn’t want blacks and whites to mix in any way whatsoever, and certainly not at their convention.

The nomination and election of John F. Kennedy was, at the time, rightfully considered a significant expansion of the American identity. Still, in 1960, no one dreamed they’d live to see an African American or a woman nominated for the presidency. There were no phone messages back then, but if there had been, no one would have dreamed they’d have to push 1 to hear the message in English, or that highway signs and supermarket labels would be in English and Spanish. What many did dream, and seriously, was that by the year 2000—which seemed a distant, magical realm—American problems like racism, poverty, and perhaps even war would be things of the past.

In 1960, the American identity was embodied, here and throughout the world, by the likes of John Wayne and Marilyn Monroe, Jimmy Stewart and Katharine Hepburn. The America that counted traced its roots to northern, Protestant Europe (except for those wild Irish). WASPs were American. Everyone else had to prove their credentials—provided, of course, that they could get in the door. The proof of who counted is in the TV commercials of the era: if you wanted to sell anything on TV, your salespeople had to look 100 percent WASP. According to Madison Avenue, and many others, everybody who wasn’t WASP must certainly want to be.

Since the 1920s, non-WASP immigration had been managed by severe quotas. Asians, as well as Southern and Eastern Europeans, were no longer welcomed with open arms. In New York City, many of my generation were the children and grandchildren of immigrants. The city’s non-WASP population was mostly Italian, Jewish, and Puerto Rican. Also among the non-WASPs were African Americans—many of whom, like James Baldwin, had grandparents who’d been born into slavery-and the well-established Irish.

My mother spent her childhood in a Sicilian village and didn’t learn English until she was about 13 and settled in Italian East Harlem. My father was born in Italian East Harlem in 1916, but English wasn’t the language of that neighborhood when he was little; he didn’t learn his “native tongue” until he was six and went to school. As a kid, I naturally considered myself white, but if I and my little brothers, with our olive skins, went somewhere in Manhattan like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, we were considered “spics”—a word we’d thought applied only to brown-skinned, Spanish-accented Puerto Ricans (whom we called “PRs”). Everyone knew that identity depended on what street you walked—in your own neighborhood, you were a normal American; everywhere else, you were not, quite.

Anyway, it was clear who the real Americans were: they looked like people in the movies and on TV, who, with rare exceptions like Sidney Poitier and Anthony Quinn, almost all looked WASP. Jews were more frequent on TV, where they were allowed so long as they were funny. Jews who were serious actors had to change their names—like Jacob Julius Garfinkle, whose screen name was John Garfield. It was okay to have an Italian name if you were a ballplayer, but Italian singers took WASP surnames: Dean Martin and Tony Bennett. Frank Sinatra was a hero in every Italian household in part because he kept those pretty vowels of his family name.

My siblings, my cousins, and I don’t speak Italian because our parents didn’t want us to have accents, since their accents had caused them no end of trouble in their youth, when they were trying to find work. The unspoken but widely held assumption of immigrants, their families, and WASP Americans alike was that we non-WASPs weren’t supposed to change America, the country was supposed to change us. We were supposed to live up to the WASP ideal.

Throughout the tumultuous changes of the ’60s and ’70s, the prevalent assumptions about ethnic assimilation proved surprisingly sturdy. African Americans made progress (of a kind); anti-Semitism became much less prevalent (or had to hide); even Italians became respectable. But these were urban developments. In small, rural communities, especially in the South, Midwest, and West, the old expectations and prejudices remained strong.

For instance, when I lit out to explore America in 1972 (never to return to the East Coast), I was having a quiet, solitary beer in a Texas Panhandle bar when four large WASP males, the very image of “the Texan,” came up to me and one of them asked, in a thick Texas accent, a question you still hear now and again: “You’re not from around here, are you?” This is less a request for information than a flat statement of fact. Before I could answer, I was asked, “Are you—a New York Jew?” I was frightened to suddenly be given the burden of upholding the honor of my Jewish friends, but the code on the streets where I grew up, in Brooklyn and the Bronx, was that a man can never back down. So I said as levelly as I could manage, “No. I’m a New York Eye-talian (mocking their accent), but I wouldn’t mind being a New York Jew, if it came to that.” Fortunately, the response was “Play any poker?” We played some cards and they let me alone thereafter, finding small, noninvasive ways to make me remember that they were real Americans, and I was, well, “not from around here”—here meaning “from sea to shining sea.”

But by the end of the ’70s, the identity of women, African Americans, and even gays had changed drastically. In the ’80s, with immigration barriers being breached on all sides, the American identity began to be transformed. By the time we reached that once-magical realm, “the year 2000,” everything to do with the concept of “American identity,” both personally and collectively, had gone so completely haywire as to become indecipherable, and most of us are more confused about our national identity than seemed possible half a century ago.

Suddenly Different

In part, the confusion about who Americans are is the result of a demographic fact: the national public discussion, meaning the mirror that the media hold up to our values and concerns as a nation, is conducted largely by Euro Americans and a few African Americans who live and work in our big, fashionable coastal cities, and who rarely interact with people unlike themselves.

So it isn’t surprising that America’s professional “thinking classes” have been blindsided by the immigration situation, the virulent anti-immigration reaction, and the “new” identity politics of race and gender—by a tectonic shift in the American identity. The same people were blindsided 30 years ago by the rise of the Christian Right, a phenomenon that surprised no one in Texas or Georgia who had functioning eyes and ears.

It seems clear then that to understand America’s crisis of identity—the fundamental changes that have occurred in the last few generations, and the thoughts and emotions that ensue from them—you need to know more of America than just its affluent coastal cities.

Consider, for instance, Lubbock, Texas.

I lived in Lubbock from January through September 1973—not as a resident, but as a drifter, taking my time passing through because I met some Lubbock-born artists and musicians of extraordinary gifts, the rebels of the town at the time. The Lubbockians I got to know were all Texans, mostly born and raised in Lubbock or in Texas Panhandle towns within a two-hour drive. This was true of the overwhelming majority of the city’s population of 100,000. Ethnically, most were some Anglo-Saxon mix, frequently with Celtic ancestry—Welsh, Irish, or Scots—thrown in, but let’s make do with “Anglo-Saxon” for ease of reference. Cherokee or Apache blood had often been added a few generations back. Many traced their American ancestry to well before the Civil War, and many of their grandparents, literally, had come to Texas in covered wagons.

In 1973 in Lubbock, Anglo-Saxons, Latinos, and African Americans didn’t mix socially (to state the obvious and put it mildly), and kept to their own neighborhoods. Once or twice, at the Cotton Club, I saw an African American male dancing with an Anglo-Saxon female; I admired their guts and feared for their safety. The only Jew I was aware of was the Long Island–born friend who’d driven me there, and she didn’t stay long. Lubbock’s cuisine in those days was limited: lots of Texas diner food, some Mexican, a Chinese restaurant, an Italian restaurant, and that was about it. Back then, Lubbock bragged about having more Christian churches per capita than any city in the world. All the Texans in town had pronounced Texas accents.

Thirty-five years later, Lubbock has doubled in size to 200,000, and I’ve been a resident for three and a half years. Like many such rural centers, the city has changed. These days, many who’ve grown up here have barely a trace of Texas in their speech; the young, especially, sound sort of San Fernando Valley-with-a-lilt. The best supermarkets in town are identical to the best in Los Angeles; they even have kosher sections and sell challah on the Jewish sabbath. There’s a market serving families from the Indian subcontinent, and lots of good restaurant food: Texan and Tex-Mex, plus Thai eateries (run by Thais who’ve been here a generation), a Vietnamese restaurant (run by Vietnamese), two French restaurants, and a fancy new Italian restaurant run by a New York Italian. There’s a mosque. And I’m told the synagogue has a visiting female rabbi.

As in LA, it isn’t rare to see people of indeterminate ethnicity in Lubbock—Asian-Latino, Middle Eastern–Irish, Euro-Asian, African–Middle Eastern, and so forth. On my street, in a down-at-heels part of town, there’s every sort of ethnicity and race, and no trouble. It’s not unusual, in any part of town, to see interracial couples of all ages and mixes, with no fuss, no self-consciousness, and no one seeming to notice. Not that there are a lot of interracial couples; it’s just not unusual and it’s no big deal. The other day, at a Mexican cafe, I saw a classic, well-dressed, West Texas Anglo-Saxon old lady, her blue-white hair in a firm bubble do. Her old-time accent rang through the room as she happily played with her half–African American granddaughter. No one noticed except me and my notebook. When that West Texas lady was born, every school, restaurant, bathroom, and bus in this state was segregated, and most Anglo-Saxon Texans meant to keep it that way.

Thirty-five years ago, Lubbock was Texas. Now a strong Texas accent is as unusual as a cowboy hat. The town still is a family-values place—conservative and Christian. You still have to drive across the county line to buy package booze, and Lubbock still advertises itself as a pure creation of the pioneers of the Great High Plains. Yet it’s become cosmopolitan; there’s no other word for it. If a place like Lubbock is no longer classically Texan, then the state is no longer what once was meant by the word Texas. That’s no small matter.

In 1973, the Texan self-image, the Texan reality, and the world’s image of Texas, were roughly approximate. In the early ’70s, the state still took its basic image from its small towns and ranches. Now its small towns are falling apart, its ranches are subsidy-addicts, and Texas no longer has an Anglo-Saxon majority.

The same is happening all over the country. When I first hit the road in 1972, accents, attire, and behavior were markedly different in different parts of the land. There was some ethnic diversity in big cities, but almost none anywhere else. All that’s changed, and the traditional images of Southerners, New Yorkers, and Texans are fading further and further from the daily reality. This is especially true of the middle class and affluent.

With the emerging candidacies of Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, we’ve all discovered the unexpected power of group identity—a sense of identity that hasn’t really been considered in traditional psychology. Psychology, like commercial marketing, has focused on the individual. The field’s interest has been the individual’s understanding and growth, while marketing has focused on the individual’s image and sense of advancement. But at this historical moment, we’re seeing, and having to deal with, how powerfully group identity works upon the individual.

In primary after primary, the people are mostly voting for someone they see as one of them: women over 40 are voting for Hillary Clinton; male Democrats and most voters under 29 are voting for Barack Obama; evangelicals voted for Mike Huckabee. People are voting against those they see as the outsider, and for those they see as best representing their group identity.

Psychology is ill-equipped to understand group identity because, for this field, it’s a new concern. As a practice and as an intellectual enterprise, psychology has rarely dealt with sociological issues like class, or historical issues like migrations. But it must, if the field is ever to come to grips with the effects of group identity on individuals. These issues enter the consulting room through individuals, but they can’t be grasped by a psychology of individuals. For instance, the virulence of anti-immigration feeling in America today can’t be adequately understood by studying an individual’s psychological history, family life, and so forth—the usual territories of psychological investigation. That feeling can only be understood in an individual’s sociological context.

The Scope of Change

Let me be concrete and specific.

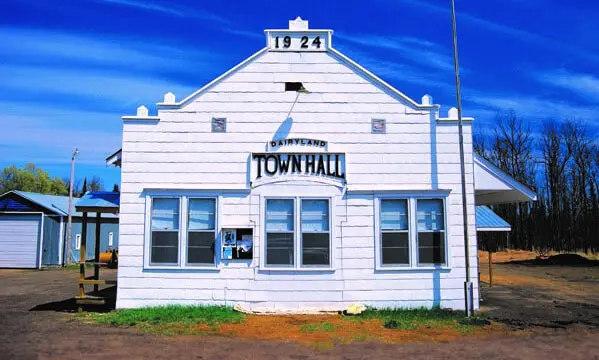

Drive east of Lubbock on Texas Route 114, a well-traveled, four-lane highway. In less than 20 minutes, you’ll cross US 62. Head north on that little two-lane, a straight line on flat land—so flat that the skyline on all sides is below eye level, and you have to look a bit down to see the horizon. You drive through miles of plains and fields—virtually treeless, and sometimes spotted with cattle—until you come upon an almost-ghost-town, one of thousands across the West and Midwest. Just a few homes nestle here, and half are empty.

A historical marker announces, “Village of Cone—Named in 1903 for J. S. Cone—Town Once Had a School, Stores, and Churches.” There’s no trace of anything now but the school: red brick, two spacious wings, windows boarded. Engraved in stone above the front doors is an inscription that confuses at first glance: “19 Cone 23.” That inscription speaks of pride and hope. The people who built that school expected something here that didn’t happen: a long, prosperous future.

Floydada, the county seat, is a few miles north of Cone. Like most county seats in such places, a well-built courthouse in the center of town marks where the action used to be. Driving the four streets that branch off from the old courthouse, I counted 55 defunct stores. Founded in 1890, Floydada’s official population is now said to be almost 4,000. Try and find them. They don’t frequent the stores downtown or the long-shuttered movie theater. The people who built this place didn’t expect this to happen. They didn’t found this town to see it all but dead by the time their grandchildren were middle-aged.

I’ve driven every state in the West and Midwest these last several years, and everywhere you go you see these barely living towns, ruins of toil, ruins of dreams, ruins of a future that people worked hard for—a future that never came. But even seeing this over and over with my own eyes, I was startled to read in The Economist recently that there are more than 1,000 ghost towns in Texas alone. The article cited the town of Thurber, once home to 10,000 people; now there are only 5.

Two years ago November, I drove Kansas and Nebraska with my friend Dave. We’d read that in many counties there were now fewer people than in the late 1800s, and we wanted to see for ourselves; we did. Prairie-grass swayed in the wind where there’d been farms. Town after town looked like what I’ve described of the Panhandle: they had different architecture, but always the beautifully built and long-abandoned county courthouse and dozens of empty stores.

I forget the name of the Kansas town where we stopped for lunch. It was like a scene in an old Western: we walked in and everybody stared as we took our seats. Dave, he could be a businessman from down the road (as, in fact, he is)—distinguished looking, tall, gray hair, casual clothes—walked into this diner alone, and he was fine. Me—maybe it’s my olive skin, maybe my gray pony-tail, I don’t know—but the people in that Kansas diner looked at me with naked, livid hatred. One farmhand couldn’t take his eyes off me. Sitting with his friends at lunch, he stopped eating and stared at me, his face trembling—trembling! I don’t exaggerate—with rage and hate. I didn’t look like anybody in the county, so I instantly became symbolic of “the enemy,” the unseen enemy who’s changing everything.

These people are watching their towns die, watching their way of life die. To put it in psychological terms: they’re watching the death of their very identity. Naturally, they cling to that identity tenaciously, but it’s hollow and doesn’t resonate anymore. They’re living the end of the dream of their parents and grandparents, and they can’t believe this could happen. Like their ancestors, they’ve worked hard. They’ve played by the rules, believed what they were taught to believe, worshipped as they were taught to worship, lived as they felt life should be lived, but they’re losing everything that matters to them. And there’s nothing they can do about it except to keep working hard, because that’s all they know.

They’re losing a way of life because of forces beyond their ken: giant agribusiness, technological innovation, globalization, politicians selling them out, a tidal wave of history sweeping them away. Republicans and right-wing demagogues play to them, so they vote for Republicans, but it doesn’t help. Liberals and Democrats rarely to talk to them and never talk with them, so why would they listen to or vote for them? “Blue state” snobs make jokes about the stupid “Red states.” These rural people aren’t stupid: they’re furious. Time has passed them by, and they don’t know why. They want somebody to blame—a useless but human need.

So I walk into their Kansas diner and in all my differentness I become a symbol of what’s pulling them down. Their kids are leaving town, their towns are dying, their leaders are failing them, and they’re helpless to stop it. They’re furious, and the likes of Rush Limbaugh and Lou Dobbs give them objects for their fury. Limbaugh and his ilk are believed by many of these people, and why shouldn’t they believe? Who else is talking to them? Who else bothers? This is a huge question when you stop to think that it’s precisely the gulf of ignorance between coastal liberals and Red-state rurals that’s determined America’s political agenda for the past 30 years.

The issue at the heart of this crisis, evidenced by the animosity between our Red states and Blue states, simply put is: we don’t yet know what an “American” is. We don’t yet know what an “American” even looks like. That identity hasn’t yet been settled by history.

From about 1930 to about 1980, the question of American identity seemed decided; but history didn’t accept that era’s definition. History moved on, though America’s self-image lagged (and still lags) far behind our historical reality.

Think of Lubbock, this supposedly right-wing city, in the middle of nowhere. If so much drastic ethnic and social change has happened here in merely one generation, try to imagine Lubbock one or two generations from now. You can’t. No one can. The same holds true across the country. The American identity is in flux, undefined, and no one knows what it’ll be in another generation, much less in two.

Nothing so disorients an individual or a people as an identity undefined, threatened, in flux. The anti-immigration frenzy is fueled by a panic of identity. Americans no longer look or sound like, and will never again look or sound like, this country’s rigid image of an “American.” As James Baldwin wrote in 1950, “The world is white no longer, and will never be white again.” Nor will it ever be male-dominated again. It will never be monocultural again. And when millions feel it necessary to pass laws that say marriage is an institution possible only between a man and a woman (something absolutely taken for granted in 1960), then clearly the world will never be “straight” again either.

Many are unhinged by these facts. Their pent-up panics, caused by myriad changes, get unleashed upon comparatively minor changes like “illegals.” But what changed Lubbock? Not illegals. Lubbock is changing because of uncontrollable tidal shifts in economics, culture, technology, and perception. For this fact is absolute: Lubbock, Texas, 1973, would never have agreed to become Lubbock, Texas, 2008. Its changes were and are irresistible.

The America-to-Come

The world will never again be the world out of which psychology developed—monocultural, white, principally Judeo-Christian. Psychology has an immense intellectual project before it. In such a world as ours today, the individual and the family can’t be understood solely in terms of the individual and the family. Psychology must greatly extend its boundaries if it’s to remain relevant and applicable.

Where are we going? What’s the world to come? No one dares say for certain, but there are indicators. I suspect it’ll look something like this:

A friend teaches third grade in a fairly affluent, liberal, private school in the San Fernando Valley. Not a decade ago, this school was overwhelmingly white, mostly of the WASP variety, with only a handful of Asian, African, and Hispanic Americans in a student body numbering about 350 from kindergarten through 12th grade. Knowing of my interest in such matters, this friend recently sent me an ethnicity breakdown of her 25 third-graders: Irish-Iraqi, Puerto Rican–Mexi-can, WASP-Japanese, Sicilian-WASP, WASP–Native American, Peruvian-Guatemalan, WASP, Jewish-WASP, Mexican-WASP, Jewish, WASP, Nigerian-WASP, Irish, Jewish, Scots, Armenian, Mexican-WASP, Korean-Chinese, WASP-Jewish, Irish-English, WASP-Filipino, Swedish, Chinese, Columbian-Irish, Jamaican-Jewish—all affluent little American citizens.

And if the Mexican-WASP grows up to marry the Korean-Chinese, or if the Irish-Iraqi grows up to marry the Jamaican-Jew, and if (as is certain) many of their offspring marry likewise—well, in America-to-come, the roots of any one family are likely to span the world and include a dizzying number of races, ethnicities, and traditions, plus every religion! In two or three generations, the purely “white” or Euro-rooted American will be the exception, rather than the rule.

That’s the future, our future, and it’s a future that our present “multicultural” and “melting pot” platitudes won’t suffice to grasp or analyze.

A panic of identity can sway politics, but politics can’t legislate identity. Such questions get decided by forces more inexorable. It’s worth repeating: Lubbock, Texas, 1973, would never have agreed to become Lubbock, Texas, 2008. Lubbock and all of America have changed beyond anyone’s power of choice. What many can’t admit is that change never stops for our convenience. History never picks you to be its exemplar, because history is never satisfied with you or me or anyone. The forces of history aren’t a matter of the past, but of what comes next. When history repeats itself, it does so in a different language or a different mix of colors.

In 1900, Henry Adams wrote of the year 2000, and, to my knowledge, he’s the only one back then who got it right: “At the rate of progress since 1800, every American who lived in the year 2000 would know how to control unlimited power. He would think in complexities unimaginable to an earlier mind. He would deal with problems altogether beyond the range of earlier society. The new American would need to think in contradictions. The new universe would know no law that could not be proved by its anti-law. It would require a new social mind.”

That “new social mind” is being created and shaped before our eyes, from the San Fernando Valley to Lubbock, Texas, and all across this continent. The task of all of us, and certainly the task of psychology—a task not chosen, but forced upon us—is to begin to understand not only what new social mind is being created before our eyes, but what new social mind is emerging in our own heads. For history isn’t a spectator sport. In varying degrees, a new social mind is being created by these forces in everyone. The effort to “know thyself” and be true to that self now involves many more variables than anyone in 1960 could have dreamed. If that’s stating the obvious, it can rightly be said that there’s nothing obvious about “the obvious” anymore.

Psychology, as a practice and as an intellectual project, must realize that the monocultural contexts out of which it arose are no more. The psychological parameters of the Jamaican-Jewish-Irish-Iranian married to the Chinese-Lakota-African-Latino, with their two Jamaican-Jewish-Irish-Iranian-Chinese-Lakota-African-Latino children, will be . . . different. The globally referenced world they’ll inhabit will be utterly different from the Euro-American world that produced today’s psychology.

PHOTO © VISIONSOAMERICA/Joe Sohm

Michael Ventura

Michael Ventura‘s biweekly column appears in the Austin Chronicle.