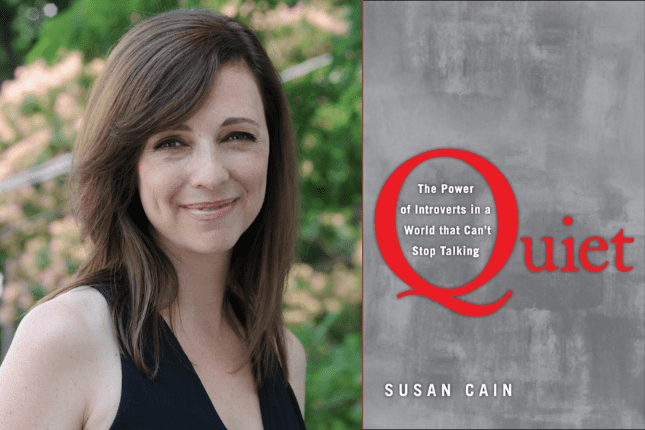

Introvert or extrovert? It’s a fundamental personality distinction most of us use to guide our decisions in choosing everything from romantic partners and friends to employees and even presidential candidates. And more often than not, we tend to give preference to the people we see as more social, gregarious, and comfortable in the limelight and in crowds. But according to self-proclaimed introvert Susan Cain, author of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World that Can’t Stop Talking, maybe it’s time the world came to appreciate the strengths and contributions of the 50 percent of Americans who are introverts.

In 2012, she gave a wildly popular TED talk in which she argued that our world has been ruled by extroverts long enough. Fueled by the response to her TED talk and the success of her bestselling book, she has started a movement called the Quiet Revolution, which promotes change in education and business that acknowledges and nurtures introverts’ unique talents. She recently found time on her way to a speaking engagement to share some thoughts on the practical challenges of helping introverts reach their full potential.

——

RH: You’ve said introversion is viewed as a second-class personality trait. Why?

CAIN: I think the answer lies deep in the roots of American history. We started off from the beginning as a kind of anti-intellectual culture that valued action over contemplation. This only intensified in the 20th century, when people started moving into the cities and having to compete in the job market, selling themselves in job interviews and on behalf of their company. That’s when what historians call the cult of personality really began to flourish, and at the same time the film industry began to offer these larger-than-life figures on movie screens who embodied what regular people were supposed to be.

Thankfully, this trend has begun turning around somewhat in recent years, in part because of the tremendous growth of Silicon Valley, which is full of successful introverts. For better or for worse, ours is a culture that values financial success, and a lot of that is being generated by quiet, contemplative people these days.

RH: You’ve suggested that the emphasis on extroversion has in some important ways had a harmful effect on society. What do you mean?

CAIN: What’s harmful is the lopsidedness of a culture that values extroversion exclusively. If you look at the financial crisis in 2008, so much of it resulted from a mentality within the finance world that it’s always good to take risks and move ahead without thinking too much about what the potential downside might be. That kind of attitude got us all into trouble. By the way, I’m not blaming the entire financial crisis on extroverts. Introverts contributed to it as well because they also bought into those cultural norms.

RH: How do you distinguish between introversion and shyness?

CAIN: Introversion is much more about a simple preference for a quieter, stimulating environment. Shyness is more about the fear of social judgment and being prone to feeling social embarrassment. You could be introverted but not be shy at all, or you could be an extrovert who’s shy. In fact, I was just interviewing Eileen Fisher, known for her extremely successful clothing line. She’d always considered herself an introvert, but as we talked, she realized that she’s actually a shy extrovert. She certainly likes people, but she feels shy and awkward when she’s around them. Over the course of our conversation, she realized that the answer to this problem isn’t seeking more solitude, but looking for more practices—such as breathing and meditation—to help her feel more calm.

RH: Many people have said President Barack Obama is an introvert.

CAIN: And he’s often criticized for not being as much of a schmoozer as presidents usually are. At the same time, he’s great at giving talks, and some introverts definitely feel comfortable on a podium because they regard it as an environment they can control. Most introverted leaders I’ve interviewed are highly aware and mindful about their need to recharge after talks or periods of socializing. So they balance that recharge time with their “on” time, giving themselves periods of quiet reflection when making important decisions, instead of feeling pressured to make them on the spot during a meeting.

RH: You talk about how the school system is set up to turn kids into extroverts. How does that happen?

CAIN: The educational system is increasingly emphasizing class participation, constantly encouraging students to speak just for the sake of saying something, whether they care about what they’re saying or not. I don’t think that’s a good idea for all kinds of reasons. For one, it’s creating a broader culture of blowharding, where children are literally being taught to speak longest and loudest, just to have the airtime.

Sometimes I get pushback from people who say things like “Don’t we have to train kids to be able to be vocal advocates for themselves? Shouldn’t we be doing that in school?” The answer is yes, but there are a lot of different ways to equip kids with those skills. We should teach kids how to be assertive or speak up in meetings, but that shouldn’t be privileged above other nonacademic skills like character, grit, and kindness. Also, we need to stop mixing up the teaching of academic material with the teaching of group participation. I was just chatting with a bright young woman who told me she failed AP Calculus because, instead of being allowed to work through problems on her own, she’d been obligated to do it in a group. One student always knew more than the others, and the less skilled students would simply defer to the more advanced one, even though they weren’t actually learning anything.

RH: Have any schools changed as a result of your efforts?

CAIN: I’ve found schools and educators to be incredibly receptive to this critique. In fact, my organization, Quiet Revolution, is launching a Quiet Schools Network. We’re working with our first cohort of 50 educators from schools all over the country to train them in how they can harness the talents of the introverted students in their classrooms. We’re training the teachers to understand and recognize the nature of individual temperament. We’re asking them to reflect on their approach to class participation and what that means for all their students. We’re helping them restructure classrooms, even rethink the physical setup of schools to accommodate students who need a quieter environment. For example, we’re helping teachers organize recess so that being part of a big noisy, massive group isn’t the only option. A quieter space, where students can go inside and play chess or do puzzles or read, would also be available. We also want to give teachers techniques to conduct a classroom discussion in ways that can comfortably draw out the introverts.

One example is the think-pair-share technique, in which a teacher poses a question, students think about it quietly on their own, then they discuss it with a partner, and then the pairs of partners are invited to share with the larger group. Whether they accept that invitation to share, each and every student—the introverts and extroverts both—have the experience of solo reflection as well as articulating their thoughts aloud. The Quiet Schools Network is a year-long program involving in-person workshops, personal coaching, and access to an extensive online portal of information, exercises, and videos with thought leaders on relevant topics.

RH: Aside from schools, where else is your revolution taking place?

CAIN: We started the Quiet Leadership Institute, which works with companies and other organizations like LinkedIn, GE, Procter and Gamble, NASA, and many others. Same idea, really. You’re helping harness the talent introverts have in the workforce and helping teams function better. A lot of our work is opening up a dialogue between the introverts and the extroverts so they can better understand each other’s needs. For example, an introvert might want to explain that he wants to keep his head down to focus and that doesn’t mean he dislikes his teammates. Meanwhile, the extrovert might explain her need to check in frequently. Together, they can work out a compromise—and they’re doing so with a shared recognition that while the other person’s needs are different, they’re just as legitimate.

RH: What do introverts bring to the team?

CAIN: A lot of it is focus and deep thinking. Introverts can stop and pause and reflect before charging ahead. We know that they tend to be highly creative, partly because solitude is a crucial ingredient of creativity. The other interesting thing is that there’s a lot of data showing that introverted leaders deliver better outcomes than extroverts do. That’s fascinating from a corporate management point of view because we also know that introverts tend to be overlooked for leadership positions. We’ve got a lot of people that would be great leaders but are not being tapped for those roles.

In fact, research by Adam Grant at Wharton shows that introverted managers achieve better outcomes because they’re better at listening to their employees, drawing out their ideas, and letting them run with them, whereas extroverts tend to be more dominant, putting their own stamp on things. Our leadership training has a Quiet Ambassador program, in which we train people not only to be more effective leaders, but also to spread insights about introverts and extroverts throughout the organization. So we teach people to identify quiet leaders who can step up and take charge. For these quiet leaders, that sometimes requires stepping outside their comfort zone. But what you find is that many introverts take on leadership positions only in the service of companies or projects that they’re passionate about, not just for the sake of being a leader. Having a true sense of passion turns out to be an incredibly valuable quality of a leader.

RH: Do you have any guidance for therapists working with clients who are introverted, or maybe introverted themselves?

CAIN: I think therapists who are introverts should make sure to give themselves breaks in between clients so they can recharge themselves and be more fully present. I’d also recommend giving thought to whether their practice is shaped by extrovert ideals or is really meeting the clients on their own terms. In general, therapists are operating within a culture biased against introversion. So how do you make sure you’re not replicating that bias within your own practice? Well, let’s say an introverted client says she’s feeling lonely. Your first instinct might be to suggest she go to more parties. But, in reality, it might be ideal instead for this client to find an activity or two that she really likes, and to focus on forming one or two deep relationships based on those interests.

Similarly, not all children need an extensive peer group. Research shows that as long as children have one or two friends, their life outcomes will be just as strong as those of a more gregarious child. But what will harm them is the feeling, conveyed by the loving adults in their lives, that there’s something wrong with their natural preference for time alone or for time playing with just one other child. I just think we all need to keep this mind in our work and our own lives.

Photo Credit: Aaron Fedor

Ryan Howes

Ryan Howes, Ph.D., ABPP is a Pasadena, California-based psychologist, musician, and author of the “Mental Health Journal for Men.” Learn more at ryanhowes.net.