When I tell women that I’ve written a book about older women, they often respond indignantly. They either insist, “I’m not old,” or “You’re not old,” as if old is a negative word, like lazy or dirty. What women mean is I won’t accept the ideas the culture has about me. We’re much more interesting, complicated, and various than any of the stereotypes the culture has for us.

With each new life stage, we find ourselves in environments that pelt us with more challenges than our current self can manage. If we don’t grow bigger, we become bitter. Yet all emergencies call for emergent behavior. And if we’re able to grow when we get to these crucible moments in our lives, our growth is qualitative, not quantitative. We become deeper, kinder to ourselves and others, and more capable of bliss.

Now, of course, the world isn’t divided into two types of women: those who grow and those who don’t. All of us fit into both groups most every day. Some of the time, we’re good copers and resilient human beings; in other moments, we’re reactive and pessimistic. And in this developmental stage of the older woman, joy and despair are as mixed together as sea salt and water. But our depth comes from experiencing a wide range of emotions, including profound tragedy, and our strength comes from mastering that which could destroy us.

Happiness is a choice, and it’s a set of skills. And once we’ve made the existential choice to be happy, we can develop the repertoire of skills we need to achieve our goals. It’s never too late to become a happier person. We become who we believe we can be. Attitude isn’t everything, but it’s almost everything. I argue that neither our genetics nor external circumstances determine our happiness. Rather, happiness depends on how we deal with what we’re given. As we age, we can see clearly that we don’t always have control, but we do have choices.

Most of the time, I can manage my expectations. I don’t give my adult children unsolicited advice. I don’t expect anyone, including myself, to be good-natured all the time. I love whom I love, not only in spite of their flaws, but partly because of them. And I’m aware that the people who love me are equally merciful. I don’t look at my horoscope; I know what I need to do to be happy. I still have my share of bad days, and I need constant reminders to be present and grateful, but I’m engaged in a hopeful process. And it’s this process, rather than a perfect outcome, that makes me happy. Perhaps the core lesson I’d like to give you is that everything is workable, even in the roughest situations. We all need to hear that right now, when we’re so demoralized, that we can find that silver current of resilience that carries us forward.

Recently, I was sitting in a sidewalk cafe with my friend Abby, who’d just gotten treatment for ovarian cancer. She’d had surgery, radiation, chemotherapy. She’d lost weight, was pale as a fish. She told me she no longer recognized herself. She felt hollowed out inside, with no markers left of the person she’d been, precancer. Her personality had been drained away, she said. But just at that moment, we got a beautiful pot of herbal tea and some almond croissants. And as Abby sipped that tea and nibbled that croissant, she smiled at me and said, “The Abby that likes croissants is coming back.”

To grow into our best selves, we need to be able to claim our own lives. We need to sort out what we truly desire and then go for it. This kind of empowerment for women is hard won. Our culture educates us to be responsible, nurturing, and available to others. Nobody teaches women to take care of themselves.

When someone needed my mother, her mother, or my aunts, they’d automatically say, “Duty calls,” or “Your wish is my command.” My Aunt Agnes would get up early on Sunday mornings, chase chickens around the barnyard, wring their necks, dunk them in hot water, pluck them, clean them, fry them; and make biscuits, pancakes, pie, eggs, and mashed potatoes. Finally, we’d all sit down around a big round table for dinner, but Agnes never sat down. She circulated around the table, making sure all the biscuits were there and people had coffee and so on. Well, there’s nothing wrong with being helpful to others. It’s not a bad life script. But we can also grant ourselves permission to think about our decisions and occasionally say no.

It’s a very hard power for women. Usually we say, “Well, maybe later,” or “I’ll think about it.” We have no training in saying no. In fact, I decided I was going to give myself the assignment to simply say no a couple of times, just for practice. The first time I did it, I thought lightning would strike me dead. It was such a powerful experience to go, “No, I don’t want to do that.”

And the power of yes is just as important. It’s the power of affirming our own needs and saying, “This is what I want, even if it inconveniences others. I want this, and I’m going to make it happen.” To be happy, we need to know how to build a good day; how we spend our time defines who we are. There’s no magical future. Today is our future. And the only real time is noticed time. All of us can find ourselves in what Michael Pollan calls default-mode functioning, and going over to-do lists. But if we learn the skill of waking ourselves up and savoring life, the present can be a great joy.

Time, attention, gratitude, and the moral imagination are the Miracle-Gro of the human psyche. If we’re growing, we experience our circle of caring to expand into a profound sense of connection to all living beings. When I was a mother of young children and working full time, I rarely slowed down for bliss. I was tired, rushed, and preoccupied with duties and chores. Now, I can move more slowly and appreciate what’s happening all around me. Most older people have more time for the luminous. As one of my older friends put it, “When I was younger, I felt bliss when I had a great sexual experience or climbed a mountain or saw the Pacific at sunset. Now, I experience it when I eat my first summer tomato or see a friend’s face light up.”

We have this three-legged cat on our property, and we feel sorry for him. He’s a hunter and doesn’t have a home. But somehow, even though we have a red-tailed hawk and a bald eagle near our house, and owls at night, this little three-legged cat has managed to survive. He’s very skinny, mangy, but he’s alive. One day—after a long, gray winter—the temperature rose by 30 degrees, and the sun came out. When I looked out my window, I saw that three-legged cat eating birdseed on our driveway. Then I saw him roll around, lolling on his back with his paws in the air, clearly blissed out, lying in a sunbeam. And I thought to myself, I want to feel as ecstatic as that three-legged cat. Now, bliss doesn’t happen because we’re perfect or problem free, but rather because, over the years, we’ve become wise enough to occasionally be present for the moment. Whatever our situations, we can have moments when we feel like that three-legged cat drenched in sunlight.

As we age, we become more aware of our place in deep time. We’re one drop of water in the flowing river of evolutionary time. We’re alive today because 30,000 generations of human mothers and fathers have taken care of us and kept us alive, kept our ancestors alive long enough to have children. We’re connected to ancient and majestic rhythms and cycles, and we’re here now sharing this moment and time with our family, our friends, our country, eight-billion other people, and all living beings. This sense for deep time and interconnection often comes to us late in life. And when we experience it, we feel deep gratitude simply for the gift of life. As May Sarton wrote, “Old age is not an illness. It is a timeless ascent. As power diminishes, we grow toward the light.”

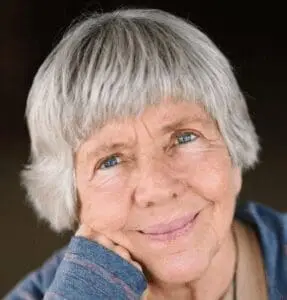

PHOTO BY SAM LEVITAN

Mary Pipher

Mary Pipher, PhD, is a clinical psychologist, author, and climate activist. She’s a contributing writer for The New York Times and the author of 12 books, including Reviving Ophelia, Women Rowing North, and her latest, A Life in Light. Four of her books have been New York Times bestsellers. She’s received two American Psychological Association Presidential Citation awards, one of which she returned to protest psychologists’ involvement in enhanced interrogations at Guantanamo.