Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

I find myself doing things these days I never would have dreamed of doing, even a few years ago. Why? Who knows? Perhaps entering my sixties has triggered some kind of surrender to emotional maturity, and with it, peculiar markers that signal a retreat from oppositional habits. Take today, for instance. I’m driving back from visiting my mother in the nursing home, and I pull into a gas station to fill my tank just because it’s the cheapest price I’ve seen around town. This is the kind of thing I used to rail against: “Who cares about the price of gas? You can’t do anything about it anyway!”

My dad liked to hold forth on such topics, with or without an audience. In fact, he could execute a marathon monologue about gas prices—which station had the best deal, whether you got any service or discount coupons, whether you had to pay for air in the tires. It would bore me to the point of begging for the mercy of an indifferent God.

Now, here I was, fresh from visiting my 91-year-old mom and chatting up a stranger on the mother of all boring topics. Not only did I top off a half-full tank, but I actually had an animated discussion with the guy at the pump next to me about how variable prices have become. At least my part was animated. He wasn’t quite as enthusiastic: “I guess they can do whatever they want,” he replied.

As I pumped fuel into my not-too-thirsty tank, I reflected on my visit with Mom. It was good to see her today. She’d lived alone since my dad had passed away, several years ago, and she finally decided (with moderate coaxing) that a life marked by the risk of falls and an inability to remember how to use the washing machine had become too much for her. We’d “gotten the most we could out of her living independently,” as her primary physician so graciously put it, so it was time to bring her closer so we could keep an eye on her. We moved her to the friendly confines of Wisconsin from her home in upstate New York, engaging in the complex and sensitive process of bringing her to a place with which she was only barely familiar. I have to admit, I didn’t welcome the transition to making her our daily responsibility. It’s just one of those things you do when your parents age, I guess.

Mom and I have battled over the years. In her prime, she was far too focused on her own agenda to care truly about me and my siblings. I envied friends who spoke fondly of their mothers, these iconic Norman Rockwell figures who sacrificed all for the well-being of their baby boys. That wasn’t my mom. Her presence was more Jackson Pollock than Norman Rockwell—a complex, brooding sophisticate, incapable of satisfaction in most endeavors, rarely offering the approval I craved.

I bristled whenever she reinvented our relationship into one only she imagined, resenting the fiction of it all. Even her appearance contradicts the maternal stereotype: at just four feet nine inches, she has a perfect wardrobe and a degree of cuteness that’s the envy of many women. She often garners all sorts of attention, even at her advanced age. At every visit to the home, someone—a nurse or fellow resident—can be counted on to say, “Isn’t your Mom just so cute?”

“Yes . . . yes, she is,” I dutifully reply.

When she arrived in Wisconsin, she believed she’d been transported to the far side of some distant, primitive galaxy: “I’m not moving to Wisconsin,” she’d decreed at a moment of lucidity, her nostrils flaring as though someone were holding a piece of Liederkranz cheese beneath it. The accumulation of years and advancing Parkinsonism had taken their toll on her, but her commitment to a social veneer had remained intact.

It took a while for her to adjust to her new circumstances. She failed at her first stop in assisted living by going AWOL several times in the snow, uncharacteristically wearing nothing but unfashionable bedroom slippers. She maintained she was going to walk to San Francisco or visit a friend in Buffalo. We subsequently moved her to a more heavily supervised nursing facility, where her attempts to escape would be met with alarms and locked doors. The second home was better suited to her infirm health and failing ability to express herself, and came equipped with a staff that’s extremely attentive without being cloying.

Surprisingly, she responded well to the structure and guidance provided in her new home, appreciating the food and the attention she received. She behaved as if it were her new country club. It was difficult, though, to see her dramatic fluctuations in functionality and mood. Ornery one day, hospitable the next; discussing the merits of Michelangelo’s sculpture as compared to Bernini one evening, and mute shortly thereafter. Her glassy-eyed stares were something I’d never before experienced, and it was hard to see her in that condition.

My visits began with the obligatory tasks: hanging pictures, attending to things in her room, trying to avoid just “spending time.” Silence might offer too many opportunities to revisit past regrets whose emotional statute of limitations had long since expired—or had it? When all the pictures had been hung and all the minor repairs completed, a 10-minute visit might seem like an hour. I frequently practiced meditative silence in her presence.

She’d nearly lost the ability to express herself adequately, one time telling me “I . . . can . . . see the . . . words in my head; I just . . . can’t get to them . . . to . . . say them.” This perfectionist, who’d demanded correct grammar from us and once had had a nearly lethal argument with my dad over the proper use of the word exceeding, was beginning to lose her power of articulation completely. She’d become vulnerable in a way I’d never expected.

One day, as I was leaving, she tugged at my arm, urging me to stay. She looked up at me, moist sorrow in her ashen eyes. “It makes me . . . sad . . . when you leave. I . . . I know you have to.” Suddenly, I failed to feel manipulated, simply valued.

We sat for a few more minutes, not saying much, just sharing space. To fill some silence, I noticed a nearby newspaper and asked her what she liked to read. “Pickles,” she said, referring to the comic strip featuring an elderly couple. “I’ll cut those out and save them for you,” I offered, knowing the strip was carried by our local paper.

After that, my visits became longer and longer, and I was more motivated to stay. On our walks around the home, I found she could be remarkably entertaining. We passed a man pushing his walker along in the hallway who was unsuccessfully trying the knobs on every door. “He’s always trying to break out,” she whispered; “I tried to tell him it’s no use.”

Today as I was leaving, we held each other close as I kissed her head. When I turned to leave, she called after me: “I . . .really . . . I . . . love you. Thank you . . . for being here with me.” I turned back and held her again, her trembling frail frame like a helpless puppy in my arms. A welcome flood of feelings consumed me, unaccustomed as I was to feeling them. I never knew what she might be doing for me when we made the commitment to care for her. Reluctantly, I pulled away and backed slowly out the door.

I moved to the parking lot, fumbled for my keys, and sat behind the wheel of my car, reflexively starting the engine, scanning the gauges, and plotting my route home through eyes blurry and damp. Tears streamed down my face—tears of gratitude, I guess, but I’m not sure. I find myself doing things these days I never would have dreamed of doing, even a few years ago.

Illustration © Adam Niklewicz

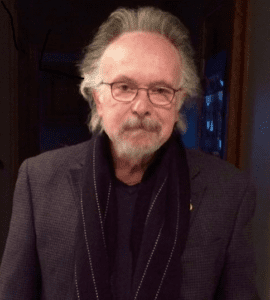

Richard Holloway

Richard Holloway, PhD, is a professor, associate chair of the Department of Family and Community Medicine, and associate dean for student affairs emeritus at the Medical College of Wisconsin. He maintains a practice as a licensed marriage and family therapist.